Summary

In late 2015 the Islamist armed group Al-Shabab forcibly abducted Hamza, a 15-year-old boy from the contested town of Merka in southern Somalia, and took him to one of the group’s training camps. After two and half months of rudimentary training with an AK-47 assault rifle, he was among at least 64 children sent to fight for Al-Shabab in an unprecedented attack in Puntland in March 2016.

Hamza, unlike many of the boys he trained with, survived the assault. He was captured by the Puntland military and taken to jail. “Four Puntland soldiers beat me,” Hamza told Human Rights Watch. “They tied my hands behind my back and legs together with a very strong rope. They beat me with their gun butts and kicked me in the chest several times. Then they threw me into their vehicle.”

After six months’ detention in Garowe, Puntland’s administrative capital, he faced trial on charges of insurrection and terrorism before a military court. He described his trial:

The military court prosecutor asked me my name, if I had fought against Puntland, where I had been captured, and whether I had a gun. I was alone, there was no lawyer.

In court, I was asked if I was guilty, and I said, yes and that I had a gun but that I wasn’t fighting. The judge said, “If you were carrying a gun, then you are part of Al-Shabab.”

He was given a 10-year sentence. He has since been transferred to a child rehabilitation center, but his sentence has not been rescinded.

Hamza told Human Rights Watch he felt doubly victimized: “I feel afraid and let down. Al-Shabab forced me into this, and then the government gives me this long sentence.”

All Somali parties to Somalia’s 25-year-long armed conflict have recruited children, using them as combatants, porters, informants or to man checkpoints. Over the last decade, Al-Shabab has recruited thousands of children, some as young as 9, into its ranks and forced many to fight.

In 2014, Somalia’s federal government committed to promptly releasing children formerly associated with Al-Shabab to the United Nations and child rehabilitation agencies.

The abuses and hardships faced by children while in the hands of Al-Shabab do not end when they come into government custody – whether surrendering, being captured, or arrested in mass sweeps. Somali government authorities hide behind an outdated and ill-functioning legal system and very real security threats to treat children alleged to have been associated with Al-Shabab first and foremost as adults and criminals, rather than as victims of the conflict.

This report is based on interviews with 15 children recruited by Al-Shabab since 2015, 10 boys held in government custody following arrests in mass sweeps, and 40 interviews with relatives of boys prosecuted by military courts, along with two dozen interviews with lawyers, advocates working with children, and senior government officials. It focuses on the government’s inconsistent and at times abusive treatment of children alleged to have been associated with Al-Shabab, particularly in Mogadishu and Puntland. It finds that the arrest and detention of children alleged to have been associated with Al-Shabab by authorities are neither a measure of last resort nor are the children held for the shortest time possible.

Since 2015, authorities across Somalia have detained hundreds of boys suspected of joining or supporting Al-Shabab. In some instances, government security forces have captured boys like Hamza on the battlefield, but most boys are arrested during security operations, particularly in mass sweeps in the capital, Mogadishu.

After arrest, whether by the military, police or intelligence, children are usually transferred into the custody of Somalia’s National Intelligence and Security Agency (NISA) in Mogadishu or on occasion Puntland’s Intelligence Agency (PIA) in Bosasso. There they are detained and sometimes interrogated while cut off from communicating with their relatives and denied legal counsel. They are held with adult detainees and sometimes held incommunicado. These due process violations are all detrimental to their safety and well-being and in violation of Somalia’s international human rights obligations for the protection of children.

In a justice system that remains heavily reliant on forced confessions, children are not spared. Children in intelligence detention in Mogadishu and Bosasso have been coerced into signing or recording confessions and threatened and on occasion beaten, at times in ways that amount to torture.

There is no consistent government treatment of children it suspects are connected to Al-Shabab. While government officials have previously admitted to detaining boys deemed high risk, other factors, including a boy’s economic status, clan affiliation and external attention to the case, also determine their fate. Many boys are eventually released without charge, often after relatives intervene and bribe officials to ensure their release. Some children are handed over to child rehabilitation and reintegration centers run by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), while others face trial before military courts for criminal charges of Al-Shabab membership, murder or conflict-related offenses.

Under international human rights law, governments are obligated to recognize the special situation of children who have been recruited or used in armed conflict, including children involved in terrorism-related activities, and provide assistance for their physical and psychological recovery and social reintegration. While children who were members of armed groups can be tried for serious crimes, non-judicial measures should be considered, and legal proceedings should be in accordance with international juvenile justice standards, taking into consideration the best interests of the child. Sentencing should prioritize rehabilitation and reintegration into society. The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, which interprets the Convention on the Rights of the Child that Somalia ratified in 2015, discourages countries from bringing criminal proceedings against children within the military justice system.

While prosecutions and imprisonment of children on security charges in Somalia is not widespread, children are being tried for Al-Shabab-related crimes in military courts, largely as adults. The courts have shown no consistency on dealing with these cases, yet basic due process, including the right to present a defense and the prohibition on the use of coerced evidence, is regularly flouted.

Human Rights Watch conducted research into nine cases in which children have been sentenced by the military court in Mogadishu since 2015, primarily where children have been charged with membership in Al-Shabab or allegations of providing logistical assistance to the armed group. In Puntland dozens of children including Hamza and children as young as 12 spent months in Garowe and Bosasso prisons and appeared before military courts since 2016. The bulk of the cases were linked to Al-Shabab’s March 2016 attack.

The report refers in particular to the following military court trials of children:

- Five children arrested in Beletweyn, sentenced by the military court in Mogadishu on January 16, 2017 to eight years on charges of Al-Shabab membership (“armed insurrection”). Sentence reportedly upheld on appeal. They are currently serving prison sentences in Mogadishu Central Prison;

- A 16-year-old boy (aged 18 according to court documents), arrested in Mogadishu, sentenced to six years’ imprisonment in late 2016 on charges of Al-Shabab membership;

- Twenty-eight children ages 15 to 17 who took part in the March 2016 Al-Shabab operation in Puntland, sentenced by the military court on September 17, 2016, to between 10 and 20 years on charges of insurrection, terrorism and association with Al-Shabab. Handed over to a UNICEF-supported child rehabilitation center in Garowe in April, but sentences not rescinded; sentences reduced on appeal to 10 years on December 31, 2017;

- Nine children and one individual qualified as a child who took part in the March 2016 Al-Shabab operation in Puntland, sentenced on June 18, 2016 to death on charges of insurrection, terrorism, and association with Al-Shabab by the military court; sentences commuted to 20 years on January 26, 2017, after they were identified as under 18 by a joint UN-government age assessment exercise. An additional two individuals were later added to this group. Handed over to a UNICEF-supported child rehabilitation center in Garowe in April, but sentences not rescinded;

- A child and an 18-year-old among seven defendants sentenced to death for the murder of three government officials on February 15, 2017 in Bosasso; commuted to life on appeal on March 23 after they were identified as 18 and under by the authorities. Currently serving prison sentences in Bosasso prison; and;

- A child among six defendants charged with membership in ISIS in Bosasso on February 21, 2017; released in May after providing evidence to the court that they were arrested while defecting from ISIS.

In Mogadishu Central Prison, boys are detained in conditions that fail to meet basic juvenile justice standards, including with no access to education.

While Somali authorities have handed over 250 children to UNICEF-supported children’s rehabilitation centers since 2015 and child protection advocates say that direct handovers from NISA have increased in 2017, this has often been only after sustained advocacy efforts by child protection advocates and following lengthy detention of the children, rather than a clear sign of the authorities’ commitment to children’s rehabilitation.

Once admitted to child rehabilitation programs, authorities, including from the security forces, have occasionally interrogated children, and their legal status has at times remained unclear: in Puntland 40 children handed over to a UNICEF partner for rehabilitation in 2017 are still serving prison sentences of between 10 and 20 years for insurrection and Al-Shabab membership, raising serious concerns that these centers could serve more as correctional facilities than rehabilitation centers.

Independent oversight of children held on security charges within the criminal justice system is limited. While government oversight has improved, international and Somali child protection advocates have very limited access to intelligence facilities, prisons, and military courts. Similarly, the number of children held for Al-Shabab-related crimes in government custody around the country is unknown and there is no systematic recordkeeping system in place.

The existing legal framework regulating cases of children charged with Al-Shabab-related crimes is at best limited and at times in clear contravention of Somalia’s international obligations. New and draft laws and policies, including a draft anti-terrorism law, risk making it easier, not harder, to detain and prosecute children for Al-Shabab related crimes without basic juvenile justice protections for children and little consistent access to rehabilitation and reintegration.

While the Somali authorities face serious security threats, current practices are not only contrary to the best interests of children but may be counterproductive in the fight against Al-Shabab and only compound public fears and mistrust in the security forces. A 14-year-old boy who was picked up in a mass sweep and detained by NISA for two and half months in Mogadishu said: “You can get caught up in a bomb attack or you get caught up in a mass sweep by NISA. We are always being stopped, questioned. Either way, you face problems. It’s like we’re always in a prison.”

As Al-Shabab continues to unlawfully recruit and use children in its fight against the Somali government, the government, including state and regional administrations, need a coherent approach to children accused of Al-Shabab-related crimes that places the best interests of the child at the forefront.

The Somali government should immediately commit to ending arbitrary detention of children, allow for systematic independent oversight of children in custody, and transfer children to child protection advocates for rehabilitation, and when feasible, reintegration.

The government should not try children accused of crimes before military courts but bring them before civilian courts according to international juvenile justice standards, granting them full due process guarantees, including prompt access to counsel and their families. Children and adults should be detained separately. Any punishment for criminal offenses should be appropriate to their age, consider alternatives to detention, and be aimed at their rehabilitation and reintegration into society.

The government, supported by its international partners, should establish a civilian oversight system, notably a child rights’ commissioner, to review all cases of children in government custody suspected of association with Al-Shabab, while committing to limited security force interaction with children once handed over to child rehabilitation facilities. It should ensure that children are never detained with adults and not held in government custody solely for their association with al-Shabab or other armed groups.

Federal and regional authorities should commit to a thorough review, with international support, of existing and draft laws and policies that relate to treatment of children formerly associated with Al-Shabab or detained for security-related offenses.

International actors in the security sector, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) should press for more concerted efforts to facilitate the handover of children to rehabilitation while helping to establish a fair and competent juvenile justice system. Partners should encourage lawmakers and authorities to criminalize and prosecute anyone found responsible for abuse of children.

Key Recommendations

Immediate Action for the Somali Government

- End all prosecutions in military courts of individuals accused of Al-Shabab related crimes while under age 18; direct the military chief prosecutor to transfer to the civilian courts all future cases of suspected child offenders including cases in which it is uncertain whether the individual was 18 or over at the time of the alleged offense;

- Ensure that children are not detained and prosecuted for their participation in the armed conflict or mere membership in an armed group without evidence of further criminal offense;

- Allow independent humanitarian agencies unrestricted access to facilities where children are detained, including intelligence-run detention facilities;

- Publicly support and ensure the implementation of the standard operating procedures for the reception and handover of children separated from armed groups (“SOPs on reception and handover”) and direct state security forces to ensure that children are handed over within the stipulated 72 hours to civilian rehabilitation and reintegration programs;

- Line ministries and the parliament should review existing and pending federal and regional legislation, including the Anti-Terrorism bill and re-codified penal code, and policies relating to the handling of Al-Shabab, to bring them in line with international standards on children’s rights and juvenile justice.

Intermediate and Long-Term Actions

- Appoint a child rights’ commissioner within the future National Human Rights Commission, in charge of overseeing the caseload of children handed over to civilian rehabilitation. The appointee should be granted unfettered access to all detention facilities in which children are detained, informed of and take part in releases from child rehabilitation centers;

- Ensure, with international support, that any children accused of crimes under national or international law allegedly committed while associated with armed groups are treated in accordance with international juvenile justice standards—notably ensuring that detention is a last resort and is used for the minimum possible time, that children are detained separately from adults, that they have access to legal counsel, that the best interest of the child is the primary consideration, and that rehabilitation and reintegration into society are prioritized.

Methodology

This report is based on interviews and other information gathered by Human Rights Watch between November 2016 and October 2017. Interviews were conducted in Somali or English, in person in Somalia, including in Mogadishu, Baidoa and Garowe, or by telephone.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 15 boys, between ages 14 and 17, who had been recruited by the Islamist armed group Al-Shabab since 2015. Eight of these children were subsequently tried by military courts in Puntland. Human Rights Watch also interviewed a dozen adults whose children had been recruited or elders from different clans who had come under pressure to hand over children to Al-Shabab.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed 10 boys who had been detained during mass government sweeps or held in government custody on security-related offenses, and 40 family members of children tried by military courts. We also interviewed lawyers, Somali and international child protection advocates, and members of international organizations working on disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR).

Human Rights Watch also conducted 10 interviews with government and judicial officials in Mogadishu, Baidoa and Garowe. In Mogadishu we met with amongst others Abdullahi Mohamed Ali “Sanbaloolshe,” the former head of NISA, Col. Liban Ali Yarow, the head of the military court, Ahmed Ali Dahir, the federal attorney general, and General Hussein Hassan Osman, the commander of the custodial corps in Mogadishu. In Garowe, we met with the late Col. Abdikarim Hassan Firdhiye, the then military court prosecutor, Mohamed Ali Farah, the director general of the Ministry of Justice, and the commander of the Garowe prison. In Baidoa, we interviewed the regional head of NISA, and Hassan Hussein Mohamed, the Interim South West Administration (ISWA) minister for disarmament, demobilization, and rehabilitation.

Human Rights Watch also sent a summary of our findings and final questions in November 2017 to the head of NISA, the Federal Minister of Justice, and the Puntland Minister of Justice but did not receive any written responses to these letters. (Copies of letters are included in the appendices section).

Human Rights Watch research focused on three military court trials in Puntland in which children were tried. While these trials have already received some level of media and international attention, they have not received scrutiny from a human rights perspective. In Mogadishu Human Rights Watch gathered information on nine military court trials implicating 16 children, since 2015. We learned about these trials, which have not received international scrutiny, through outreach to informed stakeholders, and by identifying relatives of defendants or lawyers involved in the cases. Where possible, we corroborated witness accounts with other accounts and sources, including lawyers and military court documents. Human Rights Watch did not attend any court proceedings.

This report does not document the full caseload of prosecutions of children by military courts since 2015.

Human Rights Watch informed interviewees of the nature and purpose of our research, and our intention to publish a report with the information gathered. We informed each potential interviewee that they were under no obligation to speak with us, that Human Rights Watch does not provide direct humanitarian services, and that they could stop speaking with us or decline to answer any question with no adverse consequences. We obtained oral consent for each interview and took care to avoid re-traumatizing interviewees. Interviewees did not receive material compensation for speaking with Human Rights Watch.

In this report “child,” “children,” and “boy” are used to refer to anyone under the age of 18, consistent with usage under international law. As described below, age verification in Somalia is a complicated endeavor. International standards urge authorities and judicial officials to err on the side of caution when determining ages in prosecutions. In this report, Human Rights Watch has with two exceptions relied on the age given by the child or their relatives.

The report refers to juvenile justice as the procedures, policies and laws that are applied to children who are above the minimum age of criminal responsibility and who come into conflict with the law. The Somali criminal code, which is currently being amended, sets 14 as the age of criminal responsibility. While international law does not set a minimum age of criminal responsibility, the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child states that a minimum age below the age of 12 is internationally unacceptable, and encourages states not to lower the age to 12 if it is currently set higher.[1]

This report does not examine recruitment trends, or the use and the fate of women and girls who have allegedly been affiliated with Al-Shabab; this area requires further research.

We have used pseudonyms for interviewees referred to in this report and removed identifying information to protect their identity and to minimize the very real risk of retaliation whether by Al-Shabab or government actors. Human Rights Watch also withheld identification of organizations our researchers met with that requested anonymity in order not to jeopardize their ongoing operations.

I. Context

Somalia’s Ongoing Conflict

Since the fall of Siad Barre’s government in 1991, state collapse and civil war have contributed to making Somalia one of the world’s most enduring human rights and humanitarian crises. Successive armed conflicts have resulted in rampant violations of the laws of war by all sides, including indiscriminate attacks, unlawful killings, rape, torture, and looting, causing massive civilian suffering and displacement.[2]

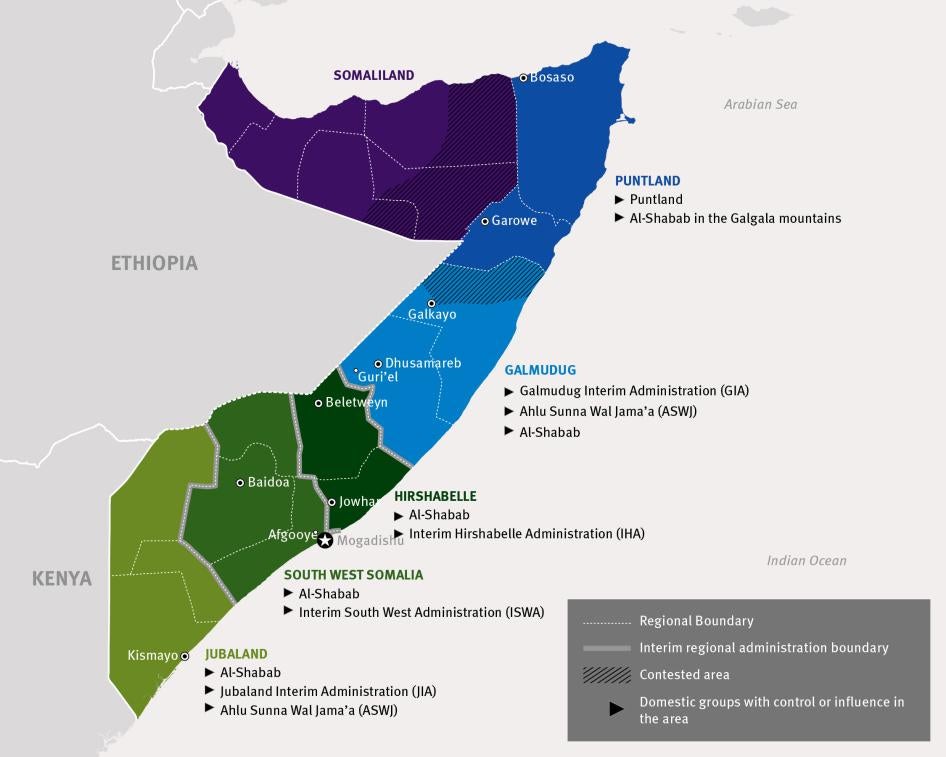

The selection of a new government and president, Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed “Farmajo,” following a protracted and controversial electoral process in early 2017 has not brought an end to the volatility, insecurity, and large-scale humanitarian crisis. The government, backed by the African Union Mission to Somalia (AMISOM)[3] and other regional and international armed forces, remains at war with the Islamist armed group Al-Shabab, which controls large swathes of territory and many key transport routes. President Farmajo announced early on in his presidency plans to step up military operations against Al-Shabab.[4] While US-supported actions in conjunction with the Somali government forces and unilateral actions against Al-Shabab have increased,[5] large-scale new military offensives by the government or AMISOM did not materialize.

In 2017, Somalia faced yet another humanitarian crisis; by the year’s end while the risk of famine was reduced, over half of the country’s 12.4 million people were still in need of humanitarian assistance.[6] While the new administration said addressing the humanitarian crisis was a priority, one million people have been newly displaced,[7] adding to the country’s existing 1.1 million internally displaced people, many of them children. Serious abuses against those internally displaced persist,[8] including forced evictions,[9] and attacks on humanitarian agencies have increased.[10]

The establishment of a federal framework is still underway, with political, geographic and jurisdictional boundaries still being negotiated by the federal and regional authorities.[11] Since 2013, four provisional interim regional states, aspiring to become federal member states, have been established: the Interim Jubaland Administration (IJA),[12] Interim South West Administration (ISWA),[13] the Galmudug Interim Administration (GIA),[14]and finally, in October 2016, Interim Hirshabelle Administration (IHA).[15] Puntland, in northeastern Somalia, declared itself a semi-autonomous state in 1998, but recognizes its status as a constituent part of the Somali state; the region has the most developed political and legal framework; Somaliland in northwestern Somalia, declared independence from Somalia in 1991.

Children in Somalia’s Conflict

Children continue to be killed or maimed by targeted and indiscriminate violence, widespread insecurity, and attacks on schools.[16] Children, particularly vulnerable to food insecurity and disease, have been disproportionately affected by the country’s humanitarian crises and large-scale displacement. During the 2011 famine, half of the 260,000 people who died were children.[17] In 2017, acute malnutrition rates among children increased by 50 percent.[18]

Throughout Somalia’s 25-year-long conflict, all Somali warring parties, including government forces, clan militia, and Islamist insurgency groups have used children in combat roles, as informants and in support roles. Somali parties to the conflict, including the national army, continue to be included in the UN secretary-general’s list of parties that recruit and use children in conflict.[19]

Poverty, destruction of livelihoods, traditional protection structures, and separation or destruction of families and lack of opportunities are key factors driving child recruitment across Somalia.[20] Many children have been orphaned or separated from their parents. While child labor is not a new phenomenon in Somalia, where children in rural areas have often been expected to help the family, conflict along with recurrent drought, have compelled many children to support their family by dropping out of school and becoming the sole breadwinner.[21]

Over the last decade, Al-Shabab has been the main perpetrator of large-scale child recruitment. Al-Shabab has used children in military operations and sought to indoctrinate children’s in its campaign against the government and foreign forces in Somalia and as a means of controlling everyday lives of people living in areas under its control.

Al-Shabab’s recruitment of children increases according to its military needs. Human Rights Watch documented increased forced recruitment of children, some as young as 10, between 2010 and 2012 in line with an upsurge in fighting in Mogadishu between Al-Shabab, AMISOM and Somali government forces.[22] Al-Shabab also used schools to recruit students and teachers to their cause and into their forces, by replacing teachers with their own members, threatening and at times killing teachers who refused to comply with restrictions on certain subjects and on their religious teachings, and at times literally pulling children off their school benches onto the front line.[23]

Ongoing Recruitment, Use of Children by Al-Shabab

Al-Shabab continues to recruit children in significant numbers. According to United Nations data,[24] Al-Shabab recruitment of children increased in 2015 after a lull in 2013 and 2014.[25] In the run-up to an unusual March 2016 attack by Al-Shabab in Puntland,[26] the group embarked on a particularly aggressive recruitment drive of children, and the UN found that during the first three months of 2017, Al-Shabab recruited 389 boys and 8 girls. The UN documented 1,915 cases of recruitment and use of children throughout 2016, double the amount documented in 2015, with 1,206 cases attributed to Al-Shabab.[27]

Al-Shabab relies on a range of more or less coercive measures to entice or force children into their ranks – including forcibly picking up children at gunpoint in the streets or using youth to entice others into joining, promising rewards.[28]

Al-Shabab has increasingly relied on the duksis (Quranic schools), which it manages, to indoctrinate children and coerce them into military training, particularly in areas and among communities where it seeks to reassert control.[29] It also recruits children into its duksis and training system via religious events, notably Quranic recital competitions.[30]

Once recruited, children are generally taken to an Al-Shabab training camp where they receive physical and light weapons training as well as religious indoctrination. Life in the camps is harsh – children who fail to obey orders, question their trainers, or attempt to escape, are often punished.[31]

Al-Shabab uses children to fight, including deploying them on the front line or in other military activities, or to run errands or carry food and provisions for the fighters. The extent to which Al-Shabab continues to rely on children to fill its ranks in more traditional combat operations became clear during the March 2016 operation in Puntland. From March 13 to 28, Al-Shabab conducted an unprecedented attack along the Puntland coastline, with some fighters later moving into Galmudug, involving hundreds of fighters.[32] The UN Security Council Somalia Eritrea Monitoring (SEMG) group described it as an apparent attempt to eliminate a faction of the Islamic State (also known as ISIS) that has been active in Puntland’s northeast.[33] According to the SEMG, 350 to 400 fighters took part in that operation, of which at least 109 were children. This number, however, does not include children killed during the operation.[34]

Existing Policy Framework Affecting Children Formerly with Al-Shabab

Current and previous Somali governments in both south-central Somalia and more recently Puntland have repeatedly offered amnesties to Al-Shabab members who leave the group.[35]The policy framework surrounding these amnesties remains vague. [36]

In 2013, the federal government endorsed the National Programme for the Treatment and Handling of Disengaged Combatants in Somalia (National Programme) with the stated aim of supporting the rehabilitation of former combatants classified as low risk.[37] While the national programme stipulates that former combatants who are captured or detained also qualify for the program, the working consensus is that only former combatants who surrender to the government qualify and enter the screening process, although there is confusion among key actors as to whether or not that is the case.[38] The national programme states that children should be handed over to UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) within 72 hours.[39]

Intelligence agencies, notably the National Intelligence and Security Agency (NISA) in Mogadishu and several other towns in south-central Somalia, take the lead in screening former combatants for the program – classifying them into high and low risk categories – and security-related investigations.[40] NISA is also currently determining the age of individuals who come into its custody.

According to a number of individuals working with former combatants programming, the screening process, its outcome, and the aim and nature of rehabilitation, require further clarity and consistency.[41]

In late 2016, the UN and other actors involved with former combatants, began to work with NISA to develop standardized screening and risk assessments to identify low versus high-level defectors.[42] There are currently no formal reception centers, and former combatants are generally screened in intelligence facilities.[43] There is no independent monitoring of the screening process.

In 2012, the then transitional federal government, signed an action plan to end and prevent child recruitment and use by the Somali National Army, which laid out a series of measures that the government should take to ensure that children associated with armed groups in government custody are accorded protection in line with international standards and not tried before military courts.[44]

In February 2014, the federal government in Somalia signed standard operating procedures for the reception and handover of children separated from armed groups (the “SOPs on reception and handover”) that stipulate that children, whether having escaped, been captured, or having been otherwise separated from armed groups, or in government custody should be handed over to UNICEF for rehabilitation within 72 hours of having been taken into government custody.[45] So far, over 250 children formerly associated with Al-Shabab have been handed over to UNICEF since 2015.[46]

The SOPs also state that debriefings with children in government custody should focus on facilitating the prompt return to their families, and should in no way serve to obtain information “under force or threat of force, real or implied.”[47] The SOPs on reception and handover do not spell out the process of release, although they do call for procedures to be established; these have not been developed to date. The SOPs do not identify or describe the role of the intelligence agencies in the process, despite the fact that in practice, as will be described below, in south-central Somalia NISA is clearly in charge of screening and interrogations of children.

The implementation of the SOPs is inconsistent, key stakeholders at times unwilling to implement them, and independent oversight of screening processes and custody is severely limited. This has left children in limbo, sometimes in intelligence facilities, prison and on other occasions in adult rehabilitation camps, for long periods.

Under its own standard operating procedures on handover of combatants, the African Union Forces in Somalia (AMISOM) have committed to ensuring a safe handover, and to keep records of any arrests and handovers.[48] However credible sources told Human Rights Watch that this was not done systematically by troop-contributing countries.[49]

II. Abuses Against Children in Pre-charge Detention

Abuses faced by children who have filled the ranks of Al-Shabab or are accused of having worked for or sympathized with Al-Shabab do not end once they escape or when government forces capture or detain them.

Under international law, governments are obligated to recognize the special situation of children who have been recruited or used in armed conflict and to treat them first and foremost as victims. The Convention on the Rights of the Child states that the arrest, detention and imprisonment of a child should be a measure of last resort and for the shortest time possible,[50] and calls on governments to establish alternatives to judicial proceedings for children.[51] Former child soldiers should be rehabilitated and reintegrated into society.

In south-central Somalia, primarily Mogadishu, and in Puntland arrest and detention of children alleged to have been associated with Al-Shabab by authorities are neither a measure of last resort nor are the children held for the shortest time possible. The process is at times abusive.

There is currently no systematic recordkeeping in place to keep track of children in government custody, and the limited data that is collected is rarely disaggregated.[52] While the UN through its monitoring and reporting system (MRM) is collecting information on detention of children on security-related offenses, UN officials told Human Rights Watch that they are not able to systematically follow-up on incidents.[53]

Pathways into Government Custody

Harsh conditions, including lack of medical care,[54] or merely missing home spur children to find ways to escape from Al-Shabab ranks despite fear of being caught.[55] An 18-year-old, recruited by Al-Shabab at 16 and later escaped, said: “There are no advantages to being with Al-Shabab. You are not with your parents. Whenever I think about my time with them, I think about all the difficulties, always fighting. Now I feel as though I have something to look forward to.”[56]

Three boys said that a particularly harsh battle in which they had lost friends prompted them to escape.[57] “There was a lot of fighting, five children died, all my friends. The rest of us got scared and ran away,” said a 16-year-old boy who escaped from Al-Shabab in late 2016. “I threw my gun away and escaped.”[58]

Others are captured or arrested during military operations and taken into government custody.

A 16-year-old who had been forcibly recruited by Al-Shabab and captured by Puntland forces during the March 2016 Al-Shabab attack said: “This was the first time I had fought. It was heavy fighting. Many were killed. Both my friends Hassan and Yusuf [boys he was trained with] were killed. I was so shocked when I saw their bodies.”[59]

Children are on occasion mistreated by authorities upon apprehension.

Four Puntland forces brutally beat me, said a 16-year-old from Merka. They tied my hands and legs together at my back with a very strong rope. They beat me with their gunbutts and kicked me on my chest several times. They then threw me into their vehicle. The rope was tight, and I was in pain. I still have a black scar on my arm.[60]

The security forces, both police and intelligence, also regularly arrest boys during security operations or random mass sweeps, sometimes detaining boys on their way home from school[61] or during house searches, on the basis of flimsy, or no, evidence, particularly in Mogadishu and on occasion in Bosasso in Puntland.[62]

According to the UN, Somali security forces arrested 386 children in 2016 during operations targeting Al-Shabab.[63] While most are subsequently released,[64] often using connections,[65] or by paying for their release,[66] as is described below a number, especially those from poor economic backgrounds or from less connected and powerful clans whose cases don’t receive attention, are held for prolonged periods before their release,[67] some are handed over to child rehabilitation centers and others handed over to military courts for prosecution for crimes of association with Al-Shabab, material support or murder.[68]

“The CID officials would ask me if I had any relatives,” said a 15-year-old orphan who said he worked as a motorcycle delivery boy and was picked up in a security operation in 2015 following an assassination in his neighborhood.

Once they realized I had no relatives looking out for me they would constantly insult me, they would say I was an Al-Shabab fanatic as I had no family and friends. Some of the others were released, but I was kept inside as no one came for me.[69]

Boys apprehended during mass sweeps, even if released, don’t remain unscarred.[70] A 15-year-old picked up by NISA and police on his way home from school during a security operation in May 2017 and held for three days with adults in a police station said:

I thought I would be protected because I am a student. But NISA and police pushed me about and put me in a car. I had never been detained before. It shook me up, I was so sad.[71]

Boys said they limited their movement after their release, and two boys told Human Rights Watch they dropped out of school fearing rearrest.[72]

Hassan, a 16-year-old detained on several occasions since 2015 during security operations, who spent over two months in NISA detention in 2015, said:

We are always being stopped, questioned. It’s mainly a problem for people of my age. When a group of youth are just sitting down outside, we get told to move on by NISA, so it’s like we’re always in a prison. You can get caught up in a bomb attack or you get caught up in a mass sweep by NISA. So either way, you face problems.[73]

Abuse of Children in Custody of Intelligence Agencies

Once in government custody, screening and interrogation of suspected Al-Shabab members or combatants, including age screening, generally happens within intelligence facilities. Human Rights Watch research found that children have been held for more than 72 hours for Al-Shabab-related crimes in NISA facilities in Mogadishu,[74] Beletweyn, as well as in PIA facilities in Bosasso. Some children described being held several months, one for over four months. In a May 18 meeting, Attorney General Ahmed Ali Dahir said: “I don’t see many cases of juveniles [in NISA detention] but there are some who are 15 or 16 years old. But in terms of our law, we don’t consider them as children.”[75]

There is currently no independent oversight of NISA’s screening process or detention. While government officials, including the attorney general and military prosecutors have access to NISA detention facilities, independent monitoring is severely limited.[76] Human Rights Watch is not aware of independent monitoring of PIA facilities.[77] The intelligence agencies therefore generally decide how they categorize children, how long they choose to keep children for and if and when they hand them over.

Ill-treatment and Forced Confessions

Human Rights Watch, the UN Security Council Somalia and Eritrea Monitoring Group (SEMG), and the United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM) have all previously documented mistreatment and occasional use of torture by NISA during investigations.[78]

NISA interrogators and guards also subjects children to coercive treatment including intimidation, threats, depriving them of the presence of their relatives, and on occasion beatings and torture, primarily to obtain confessions or sometimes as punishment.[79] A lawyer who has worked with the military court remarked:

NISA is not comfortable with the children being handed over to the parents, as they torture them and don’t want anyone to know. They force the prisoners to confess. We see cases that are horrible, some people can’t even walk.[80]

“The security guards kicked me and threatened me: ‘I know you, I know that you are Al-Shabab,’” said Hassan who was 14 when he was picked up in a mass sweep in 2015 and held in one of NISA’s detention facilities, Godka Jilaow.

They would tell me that my relatives were outside and that I just needed to sign a paper and would be released. But other inmates told me not to sign it as it was a confession, so I didn’t.[81] He went on: The hardest part was that I was very sick, and some security guards badly mistreated us. One day, inmates had refused to use the toilets, and so the guards just beat everyone. They told us to remove our shirts, bend over and then beat us with belts.[82]

Hassan was released after two months when his parents paid US$2,500 – a large amount of money in a country where half the population lives below the poverty line – via a facilitator for his release.[83]

Ibrahim, who was 16 when he was arrested in a mass sweep in early 2016 and held for several months in Godka Jilaow, described one bad beating:

They would take me out of my cell at night and pressure me to confess. One night, they beat me hard with something that felt like a metal stick.[84] I was bleeding for two weeks, but no one treated me.[85]

The mother of a 16-year-old boy who was detained incommunicado for two months by NISA at Barista Hisbiga in mid-2015 described particularly bad wounds on her son’s body:

I found him in Mogadishu Central Prison. When I saw him, he couldn’t walk. He said he was beaten every night, and especially beaten on his legs. He had injuries on his legs. His ankles and knees were swollen, he couldn’t even stand to greet me. He had to be assisted by other prisoners.[86]

Government officials that conduct visits to NISA facilities and a defense lawyer involved in military court proceedings told Human Rights Watch that they had not come across cases of mistreatment in the latter half of 2016, when Gen. Abdullahi Gafow Mohamud headed NISA.[87] Human Rights Watch received allegations of ongoing mistreatment in NISA detention and found no evidence of actions being taken to investigate past allegations of abuse.[88] Positively, NISA have recently appointed a legal and compliance officer; however the exact mandate of the post is unclear.[89]

A 15-year-old picked-up in a sweep in 2017 and held for two months in Barista Hisbiga described his interrogations: “The interrogators asked me about Al-Shabab, they asked me if I had carried a gun. I was questioned once a week, and they used to hit me on my neck with sticks and threaten me.”[90]

The father of 16-year-old Ali detained by NISA in 2016 said that his son was held for 10 days by NISA in a house before being brought to Godka Jilaow. “They threatened him the first few days. He told me: ‘They said unless I confess to being with Al-Shabab they were going to beat me. To save my life, I confessed.’ They recorded his voice and then got him to sign a confession and fingerprinted him.[91]

On December 28, 2016, seven individuals, most originally from south-central Somalia, were arrested in Bosasso, following the killing of three high-ranking officials.[92] The seven, including Mohamed Yassin Abdi who officials would later qualify as a child, were held for a month without access to their families or lawyers in PIA detention, during which they recorded and signed confessions.[93] Relatives and a lawyer of the seven said that at least one of the defendants (not the one officially identified as a child) had been tortured during this period, and that they saw marks from what they described as electroshocks on his scrotum.[94]

Lengthy Pre-Charge Detention

Despite the SOPs on handovers that stipulate that children should be handed over to the UN and its partners within 72 hours of coming into custody of security forces, Human Rights Watch found that in both Mogadishu and Bosasso, children have been held with adults for prolonged periods in pre-charge detention in intelligence facilities.

International standards provide that children who are deprived of their liberty should be brought before a competent authority within 24 hours, and thereafter at least every two weeks to review decisions to extend pretrial detention. This standard applies to all forms of detention, including administrative detention on security grounds.[95]

Somalia’s federal constitution spells out that a person must be brought before a competent court within 48 hours of arrest. [96] According to the Code of Military Criminal Procedure, a person can be held for up to 180 days in remand (pretrial) detention.[97] Somalia’s criminal procedure code states that an individual in custody must be brought before court every seven days.[98]

Several government officials acknowledged that NISA holds detainees for lengthy periods but justified this as necessary to “extract information.”[99] A senior NISA official told Human Rights Watch: “We can’t let the detainees go within three weeks. We want to extract information. But we need to find legal ways. We currently have detainees in here for more than three months. It’s not our job to have people in here for three months.”[100]

Children, their relatives and lawyers consistently told Human Rights Watch that they were held weeks and up to four months before being released or transferred to the central prison on remand or after sentencing.[101]

Detainees in both Mogadishu and Puntland are not systematically brought before a court during this detention, as legally required, and therefore denied the possibility to challenge their detention or seek bail.[102]

Military court prosecutors in Mogadishu told Human Rights Watch that they now have an office at NISA to oversee cases that fall within the court’s jurisdiction, and regularly grant investigators additional time.[103]

Lack of Access to Relatives and Lawyers

Contrary to international standards and Somalia’s provisional constitution, intelligence agencies in Mogadishu and Puntland hold children without access to family or legal counsel.[104] None of the boys interviewed by Human Rights Watch had seen their parents while in NISA detention. The authorities do not contact parents to inform them about their child’s detention.[105] The handful of relatives who told Human Rights Watch that they had seen their child while in NISA detention said they had had to use personal connections within NISA,[106] or had paid a bribe – or both.[107]

Despite making numerous requests to the authorities and visits to detention facilities, relatives are often unable to even get confirmation of the location of their children, which may amount to an enforced disappearance, defined in international law as any deprivation of liberty by state agents, followed by the authorities’ refusal to acknowledge the detention or concealing of the fate or whereabouts of the person.[108]

Most relatives told Human Rights Watch that they only found out about the whereabouts of their children and were able to visit the children once they were transferred to the central prison in Mogadishu and Bosasso, appeared before court, or were released.[109]

In Puntland, Human Rights Watch documented two cases since late 2016, in which the intelligence agency held children without access to their relatives or to a lawyer for over a month.[110] The father of a 17-year-old arrested by the Puntland security forces on December 3, 2016 reportedly when defecting from ISIS and held for over two months in PIA detention in Bosasso said: “We tried a lot to get in touch with him, but didn’t manage to speak to him. He was interrogated with no lawyer and he was not arraigned in court.”[111]

Intelligence officials and military court prosecutors interrogate children without the presence of lawyers.[112] Abdi, a 16-year-old boy who was among 54 boys held in Garowe Central Prison for six months before appearing in court, said:

We were taken to the court building five times. The first time, they asked my name, family name, how I joined Al-Shabab and where I had been taken. I was alone during the interviews. The next three times, I was interviewed by different people, most were from the court.

I was interviewed twice by two intelligence officials. They asked about how many Al-Shabab members there were, my family’s numbers, background. They also took some photos of me. I was very afraid that I would be sentenced to death. They didn’t explain to me what the interrogation was about. I found out about my 20-year sentence on the day of the hearing.[113]

One of the lawyers who represented Abdi, Hamza and 27 other children in Puntland in September 2016 on charges of insurrection and affiliation with Al-Shabab said: “We raised the fact with the court that there were confessions, and that these were illegal as we had not been present, but the court didn’t respond or follow up on our concerns.”[114]

Harsh Conditions, Detention with Adults

Boys are detained in dire conditions with adults in NISA detention facilities in Mogadishu.

Four boys detained since 2016 said they were afraid of the adult detainees in their cells and of a reigning atmosphere of violence.[115] Ibrahim, 16, who was detained for four months, said: “The detainees used to beat each other. This happened to new detainees, for the first few weeks. One night, when I was new to the cell, a man tried to rape me.”[116] Another boy said he was slapped by a guard when he raised concerns about the adult detainees.[117]

Detainees are held in cells with no windows, limited natural light and no fresh air. The detainees compete for space inside of the cells. “The cell was too small for us all to sleep, so we used to take turns sleeping,” explained Ibrahim. [118] A 15-year-old held in Barista Hisbiga in mid-2017 said he suffered from “excruciating” headaches, for which he received no medication, because he couldn’t sleep at night.[119]

Children have no access to educational or recreational activities and are held for days on end in their cells. Detainees are only taken outside their cells to use the toilets, or when taken for questioning. Detainees also eat inside their cells. Sometimes, access to the toilets is restricted.[120] A boy who had diarrhoea, he believed because of the food, while at Godka Jilaow said: “Twice the guards refused to let me go to the toilet. They accused me of plotting something while in the toilet. I held it up, suffered a lot but after I pleaded with them they eventually let me go.”[121]

Use of Children as Informants

In a 2016 interview with Washington Post, a US newspaper, former NISA director Col. Abdirahman Mohamed Turyare acknowledged that NISA had used children as informants – notably working to “point out” suspects during security operations.[122] Some of the children were in Serendi rehabilitation camp, described in more detail below, at the time.[123]

Following the release of the article, an inter-ministerial fact-finding assessment confirmed the allegations but stated that the practice stopped in 2014.[124] In its June 2016 report, the inter-ministerial committee recommended that underage Al-Shabab members in custody have their cases expedited and sent to “age-appropriate centers.”[125]

Human Rights Watch did not find evidence of children being used as informants during recent security operations. Yet, several relatives of boys detained by NISA since 2015 told Human Rights Watch that NISA investigators had sought to coerce their children into working with them while in custody or prison.[126]

The father of 16-year-old Ali detained by NISA in 2016 and held by NISA for 10 days in a house and coerced into confessing said: “After my son confessed, he told me they stopped beating him. But he told me: ‘They asked me to work for them. When I refused they transferred me to Godka Jilaow.’”[127]

Human Rights Watch is not aware of oversight measures to ensure that children in government custody are not used as informants. In a May 2017 meeting former NISA director Abdullahi Mohamed Ali “Sanbaloolshe,” who also headed NISA for two months in 2014 when NISA was found to be using children from Serendi as informants, said: “We need a degree of “professionalism” from our sources. I have the profile of everyone we use, as I need to clear them. I am not aware of children within the [informant] system.”[128]

III. Military Court Prosecutions of Children

Since 2011, the military court in south-central Somalia has tried suspected Al-Shabab insurgents and supporters beyond the jurisdiction of the Somali Military Code of Criminal Procedure.[129] Human Rights Watch has previously documented that proceedings before Somalia’s military courts restrict defendants’ rights to obtain counsel of their choice, prepare and present a defense, receive a public hearing, not incriminate themselves, and appeal a conviction to a higher court.[130] The courts continue to sentence people to death following proceedings that fail to meet basic fair trial standards. In Puntland, the former president gave the military court jurisdiction over Al-Shabab and terrorism-related crimes in 2012.[131]

Throughout Somalia, intelligence officials and military prosecutors prosecute children for Al-Shabab-related crimes in military courts, typically as adults.[132] While trials of children for security offenses before military courts in Somalia are not common, Human Rights Watch found that since 2015, the military court in Mogadishu has sentenced at least 16 boys between 14 and 17 years old to prison time ranging from six years to life.[133] In Puntland, at least 40 children age 15 and above have been tried by the region’s military court, and 39 sentenced to between 10 years and life imprisonment since 2016.[134] Ten of the 39 were initially sentenced to death, in violation of the international law prohibition on executing child offenders,[135] before their sentences were commuted on appeal.[136]

In Mogadishu, the cases of children involve allegations of Al-Shabab membership and material support to Al-Shabab. In Puntland, the bulk of the cases were linked to Al-Shabab’s March 2016 attack and trials of children for alleged involvement in conflict-related offenses, along with one case in which children were accused of Al-Shabab membership and murder.

Independent trial monitoring is very limited. While the UN spent considerable time and resources following the detention and military court trials of the 64 children captured in Puntland after the March 2016 operation, funding legal aid for the defendants, the UN has only recently started engaging with the military court trials and officials in Mogadishu and neither the UN nor child protection advocates are currently monitoring trials, which reduces scrutiny of cases ending up before this court.[137]

|

Puntland/Galmudug Caseload –Discrepancies in Practices Across the Country The treatment of children following the Puntland and Galmudug fighting in March 2016 highlights discrepancies in practices across the country, with only some children initially handed over to UNICEF-supported child rehabilitation centers. In contrast, in Puntland – which does not officially recognize the SOPs on handover signed by the federal government and uses its own – problematic – legal framework to try children associated with Al-Shabab. Following the March 2016 Al-Shabab attack, Puntland authorities said they had 64 children in custody while authorities in Galmudug said they had 44.[138] The children identified by the authorities as children in Galmudug,[139] were handed over to a UNICEF-supported child rehabilitation center in Mogadishu in May 2016, after two months in detention.[140] In Puntland, in June 2016, 43 defendants, including 12 who would later be identified as children,[141] were sentenced to death and sent to Bosasso prison. On January 26, 10 had their death sentences commuted to 20-year sentences on appeal.[142] Two others were later identified as boys. On September 17, 2016, 28 boys held in Garowe prison and identified as ages 15 to 17 were sentenced to between 10 and 20 years. In October 2016, 26 children determined to be under age 15 were handed over to a UNICEF-supported rehabilitation center in Mogadishu after seven months in detention.[143] In April 2017, 40 children, including the 28 sentenced in September and 12 whose death penalty sentences had been commuted, were handed over to a UNICEF-supported new child rehabilitation center in Garowe. According to the UN, their sentences have not been overturned although the sentences of the 28 were reduced on appeal on December 31, 2017.[144] |

Unlawful Confessions, Evidence Obtained Under Coercion, Torture

Under the Somali criminal procedure code, confessions can only be accepted in court if the judge believes the confession was made voluntarily.[145] The Convention against Torture, which Somalia ratified in 1990, obligates governments to ensure that “any statement which is established to have been made as a result of torture shall not be invoked as evidence in any proceedings.”[146]

The head of the military court in Mogadishu and other senior military court officials told Human Rights Watch at a March 4, 2017 meeting that “they recognized that confessions are problematic” and did not accept any confessions unless made before the court.[147] A handful of relatives of children tried by the court and a lawyer in Mogadishu said that recorded confessions obtained under coercion were still being admitted.[148]

The father of 16-year-old Ali attended the hearing in which his son was sentenced to six years’ imprisonment based on an alleged coerced confession:

The judge did not question my son, nor have any witnesses. I was not asked any questions. No one mentioned that the boy was under 18, the judge was only going with the confessional letter.[149]

Lawyers involved in the case of seven defendants sentenced for murder of three government officials in Bosasso said that the confessions obtained under duress were admitted as prime evidence before the court.[150] In a May 2 letter from the Ministry of Justice, Religious Affairs and Rehabilitation to International agencies and partners in response to concerns raised about the case, the minister pointed to “video evidence of their admission of the crimes” as key evidence of the fairness of the trial.[151] A lawyer involved in the case said the first instance court refused to look into allegations of torture or exclude the evidence made as a result of the torture, and when concerns were raised by defense lawyers at the appeal level, the court failed to take it into account in their final decision. Human Rights Watch did not find any evidence that the authorities took steps to investigate and penalize the officers who allegedly tortured the detainees.[152]

In only one case documented by Human Rights Watch did the military court in Mogadishu overturn on appeal a verdict of two children for murder based on a coerced confession.[153] The lawyer who represented the two boys at the appeal level after the boys’ relatives sought legal counsel said: “My clients were told they would be released if they confessed. They were held for three months in NISA detention where they were intimidated and beaten, and forced to confess on tape.”[154]

Age Determination

Wrongful age determination may prevent a child from benefiting from the rights and protection accorded to them under international law. UNICEF guidelines on age screening underline that a child’s consent should be requested, call for the best interest of the child to be taken into account and benefit of the doubt to be applied, for qualified practitioners to conduct the assessment, for the child to be accompanied by a guardian and call for an appeal process to be established whereby children can dispute the outcome of the assessment.[155]

Judicial officials, lawyers and child protection organizations repeatedly highlighted the difficulty of age determination in a country where official documentation is scarce, and resources limited. International standards urge authorities to give the benefit of the doubt to juveniles when questions of age arise.[156] Prosecutors and judges in Somalia, however, don’t appear to apply such caution.

An international observer raised concerns about NISA officials’ lack of expertise in age determination. The observer said: “Security forces ‘prefer’ to err on the side of them being adults.”[157] For the first time, in 2017 NISA received a training on age determination provided by UNICEF and UNSOM.[158] UNSOM officials also told Human Rights Watch that they encouraged NISA screeners taking part in workshops around the development of screening protocols to grant children the benefit of the doubt.[159] Human Rights Watch’s assessment of trials of children before the military court, all of which had initially been processed by NISA, raises concerns about how age is determined during investigations.

Prosecutors and courts listed children as 15 years and above, even when their families and lawyers questioned the age given to them.[160] Concerns raised by relatives about the age of the child don’t appear to systematically factor into final judgments or sentencing.

Human Rights Watch did not identify any independent age screening processes of cases before the military court in Mogadishu.

In only one of the three cases in which children were tried by the military court in Puntland investigated by Human Rights Watch was a thorough age screening process conducted, involving government and UN officials.[161]

In the case of seven defendants accused of murder in Puntland, relatives of the defendants told Human Rights Watch that most of the defendants were under 18 years of age. No independent age verification exercise was conducted, although the government stated that it had followed up on the case with the military court.[162] A lawyer involved in the case said:

Ages that were said in court were exaggerated. The person determining the ages was the same person who arrested them. The parents were not asked the age. We didn’t bring in doctors to determine the age.[163]

Right to Legal Counsel, Guardians, Preparing and Presenting a Defense

As with adults facing military court trials in Somalia, basic procedural rights, which are strengthened for children under international law, are rarely respected. The capacity of children tried before the military court to exercise their right to counsel of their choice and prepare a defense remains minimal. In both Mogadishu and in Puntland, lawyers with limited qualifications represent defendants.[164] Independent counsel is rarely provided unless family members or international actors reach out to lawyers themselves to ensure representation, most often on appeal.[165]

In Puntland, even when legal assistance is provided to children, they often have very limited opportunities to discuss their case with their lawyer and to adequately prepare a defense. In the group trial of 28 boys sentenced on September 17 in Garowe for insurrection and terrorism, eight boys told Human Rights Watch that they only met the lawyer after sentencing, and that the lawyers only spoke to two in the group.[166]

In Puntland, while judges offered defendants a brief opportunity to speak in both the case of the 28 children in Garowe in September 2016, and the case of the seven sentenced in February 2017, time was very short and, in neither case did the children’s testimonies appear to be taken into account.[167]

While in Mogadishu, relatives are often told by prison officials and military court lawyers about forthcoming proceedings,[168] but parents are not systematically informed and permitted to be present when their children are tried and sentenced.[169] Several relatives said they only found about their child’s sentencing when it was reported on the evening news on television.[170] The father who said his son was 17-years-old at the time of sentencing said: “Instead of putting youth before military courts, they should be taken to civilian courts so that they have relatives and lawyers.”[171]

Sentencing and Right to Appeal

The criminal procedure code stipulates that children between 14 and 18 will receive reduced sentences.[172] However, it allows courts to impose life sentences on children for crimes against the state.[173] International human rights law discourages life sentences for child offenders.[174]

Sentences by military courts of children documented by Human Rights Watch, particularly in Puntland, were often harsh, failing the standard of last resort and shortest time necessary. On March 23, in the case of the seven defendants accused of killing three government officials, the appeal court in Bosasso upheld the death sentence against five of the defendants identified as adults and commuted the sentences of two, Mohamed Yassin Abdi and Daud Said Sahal identified as 17 and 18, to life in prison.[175]

In the March 2016 attack case, the boys identified as 15 years old and above were handed heavy sentences ranging from 10 years to the death penalty. The death sentences were later commuted on appeal to 20 years and the sentences of the 28 initially held in Garowe reduced on appeal in December 2017.[176] According to the ruling, the sentencing was based solely on the basis of their age.[177] The court does not appear to have considered forced recruitment as a mitigating factor even though several children said they told the court they had been forced to join Al-Shabab and the lawyers representing the children argued for coercion to be taken into account.[178]

In Mogadishu, children have been sentenced as adults including solely for their membership of the group. In December 2016, security forces arrested five boys ages 14 to 15 in Beletweyn and NISA took them into custody.[179] According to relatives, Al-Shabab had recruited at least two of the five boys in 2016 by force.

Despite the SOPs on reception and handover, NISA did not contact the UNICEF-supported partner in Beletweyn. Instead, the boys were transferred to NISA detention facilities in Mogadishu.[180] On January 16, 2017, the military court in Mogadishu sentenced the five boys, and an adult arrested with them, to the standard sentence for Al-Shabab membership for adults – eight years. The boys are serving their sentences in Mogadishu Central Prison. [181]

In Mogadishu, relatives of children sentenced by the military court told Human Rights Watch that they were often reluctant to appeal as they had been informed, including by the court’s lawyers, that appeal hearings rarely brought about a positive outcome.

Child Detention in Prisons

Record keeping in prisons in Somalia is disorganized and there is currently no systematic record keeping of children.

A UN official estimated in late 2016 that out of roughly 2500 prisoners across the country, 100 are children. He noted, “As there are no juvenile justice facilities in south-central Somalia or Puntland, courts are reluctant to confirm if an offender is under 18. Most list the juveniles as adults. Any information we have on actual numbers in prisons only refer to adults, although we know from our visits that there are clearly minors.” [182]

Detention monitoring is limited. UNICEF and other UN protection agencies do not have regular access to prisons in the country, require permission to visit, and do not have any access to intelligence detention facilities. Somali legal aid organizations that are visiting detention facilities in Mogadishu are generally only given access to detainees identified by officials or when relatives reach out in order to get legal counsel.[183]

According to Human Rights Watch research, at least 79 children have been imprisoned for Al-Shabab affiliation and related offenses since 2016 in Puntland and south-central Somalia. As of May 2017, at least nine children were serving prison sentences for Al-Shabab-related crimes, five solely for their alleged affiliation, the rest were either handed over to child rehabilitation centers or released. Given questions around age determination, described above, and lack of data, the number is likely to be much higher.

According to lawyers and monitors who have visited Bosasso prison since 2016, in which at least 13 children have been held for security offenses, children are held with adults, in violation of international legal requirements.[184] Human Rights Watch also received reports of four children being held for security-related offenses in Baidoa in late 2016 but was not able to confirm these reports.[185]

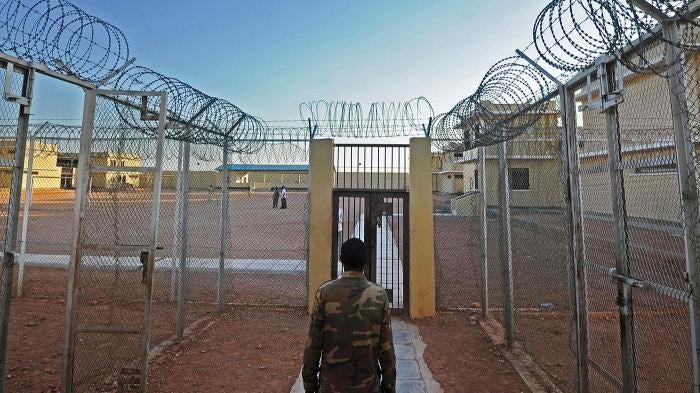

Human Rights Watch visited two prisons in Mogadishu and in Garowe where children alleged to have been members of Al-Shabab are currently serving prison sentences.[186]

Children in Mogadishu Central Prison

At time of Human Rights Watch’s visit in May 2017, prison officials said they were holding 17 children in a juvenile cell separate from adults. Human Rights Watch counted 15 in the cell. Eight have been charged with Al-Shabab-related offenses, including the five boys arrested in Beletweyn.[187]

The children in the juvenile cell sleep separately from adults, but they mingle with adults in a common area during the day including during meal times,[188] meaning that the international legal prohibition against commingling of children and adults is not observed.[189] In the juveniles’ cell, each child has a mattress on the cement floor, although officials pointed to bunk beds that were being built for the juvenile section. The previous commander of the prison, Maj. Gen. Bashir Gobe, had, according to officials, some relatives of detainees and observers, brought some improvements to the living conditions.[190]

Children appear to have little opportunity for physical exercise apart from playing in a large uncovered open-air courtyard that adults also access. When Human Rights Watch researchers visited they found all the children inside the cell on their mattresses in the middle of the day. As of May 2017, children in Mogadishu Central Prison did not have access to any form of education, although prison officials said they were planning to start classes and had allocated a cell for that purpose.[191]

Relatives of boys in Mogadishu Central Prison not held in the juvenile cell repeatedly said that prison officials use a solitary confinement room known as the “dark cell” as punishment, including for talking on phones.[192] The father of a defendant sentenced to life as a child in 2014 said: “He can’t speak about the conditions in the prison, as he is scared of being put in the dark room.”[193]

Others raised concerns about limited access to medical attention.[194]

Children in Garowe Prison

At time of Human Rights Watch’s visit in December 2016, 28 children were detained in Garowe prison in a section separate from adults.[195]

The Puntland authorities had previously detained an additional 26 children, identified as between 12 and 14 years old, for seven months there. The children had all initially been held with adult inmates until prison officials transferred them to a separate block.[196]

The children sleep in bunk beds in cells based around a large uncovered courtyard.

The boys attended formal education classes in the morning five times a week, which the boys were particularly happy about. Human Rights Watch also observed the children playing football in a large courtyard, and the boys said that they regularly played both in the main courtyard and inside the juvenile section.

Children complained about food and said they had three meals only three days a week, and only two meals for the remaining days, comparing this to other prisoners from the region whose families were able to bring food to them.[197]

Boys described one occasion either in April or May 2016 when about 10 guards beat them as a form of punishment.[198] One 16-year-old from Bakool told Human Rights Watch:

Everyone was beaten that day including the young kids [ages 12 to 14] who were transferred to Mogadishu. We were beaten because we were shouting inside the rooms. Some also peed inside the rooms and the guards were angry with us. They were around 10 men who were beating us. They were beating us using sticks and black plastic tubes.[199]

None of the children interviewed by Human Rights Watch were from Puntland originally and so none had seen their parents since being detained, although an NGO was paying for them to call relatives weekly. A 16-year-old from Lower Shabelle, who was forcibly recruited by Al-Shabab during a Quranic reading ceremony that his father had encouraged him to take part in told Human Rights Watch:

My father was sad the last time I talked to him. He told me that he couldn’t help me get out. I did not call my mum because I am sure she would cry and I don’t want to stress her by talking to her.[200]

The distance from their families weighed on most of the boys Human Rights Watch interviewed. “I miss my parents and would like to see them,” said a 16-year-old who was forcibly recruited by Al-Shabab on the pretense of being taken to a duksi. “We wish someone could change the length and place of our sentence.”[201]

IV. Rehabilitation

The 2007 Principles and Guidelines on Children Associated with Armed Forces or Armed Groups (the “Paris Principles”), described below, provide that the release, protection and reintegration of children unlawfully recruited or used must be sought at all times,[202] and that during release, children should be handed over to “an appropriate, mandated, independent civilian process.”[203]

Serendi and Adult Rehabilitation Centers

As part of the government’s program for adult former combatants, it has established with international support four transition centers to host and provide rehabilitation to disengaged Al-Shabab combatants who, in theory, have been classified as low risk.[204]

The first rehabilitation center was set up in 2012 at Serendi in Mogadishu.[205] The center accommodated both adult and child former combatants.

Independent oversight and access to the center for the first two years was severely restricted.

In August 2014 the UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General (SRSG) on Children and Armed Conflict, visited the center and subsequently publicly criticized the treatment of the 55 children who were in Serendi at the time, including that they had been detained alongside adults, not been charged with any crime, and not been given the opportunity to challenge their detention.[206] The SRSG spoke to one boy who had been in the center for three years without contact with his family.[207]

The SRSG questioned the process whereby children ended up in Serendi and highlighted that most children she interviewed during the visit said they were not former combatants, but children arrested by security forces during mass security operations.[208]

In a follow-up visit in 2016, the SRSG received allegations of other serious abuses against the children while they were detained in Serendi, including their use by intelligence forces during security operations, and sexual and physical abuse.[209] In September 2015, following significant international pressure on the government, 64 children in the camp were handed over to a UNICEF-supported NGO in Mogadishu.[210]

Several investigations were conducted both by the donor governments and the Somali government into the allegations.[211] None of the reports were made public. Key actors involved in former combatant programming and the Serendi camp told Human Rights Watch that they were unaware of any prosecutions for abuses that took place at the time.[212]

Following the international outcry of treatment of children at Serendi, at present children are not supposed to be admitted to adult rehabilitation centers.[213] Individuals involved in programming at Serendi told Human Rights Watch that intake procedures have been put in place to prevent children from being held there.[214] According to child protection advocates, NISA officials have more regularly handed over children in Mogadishu and more recently in Baidoa directly to UNICEF-supported child rehabilitation centers.[215]

The International Organization for Migration (IOM), which manages centers for adult former combatants in Baidoa and Kismayo, told Human Rights Watch in March 2017 that they only have an informal agreement with the authorities and UNICEF in Baidoa to hand over children to the UNICEF-supported partner if children turn up in the rehabilitation centers. IOM also said that there were no formal oversight mechanisms in place to ensure children are not being held in their centers.[216]

Children Rehabilitation Centers, Programs

There are currently no state-run child or juvenile rehabilitations centers in Somalia. Alongside the adult centers for former male combatants, UNICEF-supported child rehabilitation centers run by NGOs have been established in Mogadishu, Baidoa, Beletweyn, Afgooye, Kismayo and more recently Garowe.