(New York) – Chinese authorities in Xinjiang have been systematically changing hundreds of village names with religious, historical, or cultural meaning for Uyghurs into names reflecting recent Chinese Communist Party ideology, Human Rights Watch said today.

Human Rights Watch research has identified about 630 villages where the names have been changed that way. The top three most common replacement village names are “Happiness,” “Unity,” and “Harmony.”

“The Chinese authorities have been changing hundreds of village names in Xinjiang from those rich in meaning for Uyghurs to those that reflect government propaganda,” said Maya Wang, acting China director at Human Rights Watch. “These name changes appear part of Chinese government efforts to erase the cultural and religious expressions of Uyghurs.”

In joint research, Human Rights Watch and Norway-based organization Uyghur Hjelp (“Uyghur help”) scraped names of villages in Xinjiang from the website of the National Bureau of Statistics of China between 2009 and 2023.

The names of about 3,600 of the 25,000 villages in Xinjiang were changed during this period. About four-fifths of these changes appear mundane, such as number changes, or corrections to names previously written incorrectly. But the 630, about a fifth, involve changes of a religious, cultural, or historical nature.

The changes fall into three broad categories. Any mentions of religion, including Islamic terms, such as Hoja (霍加), a title for a Sufi religious teacher, and haniqa (哈尼喀), a type of Sufi religious building, have been removed, along with mentions of shamanism, such as baxshi (巴合希), a shaman.

Any mentions of Uyghur history, including the names of its kingdoms, republics, and local leaders prior to the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, and words such as orda (欧尔达), which means “palace,” sultan (苏里坦), and beg (博克), which are political or honorific titles, have also been changed. The authorities also removed terms in village names that denote Uyghur cultural practices, such as mazar (麻扎), shrine, and dutar (都塔尔), a two-stringed lute at the heart of Uyghur musical culture.

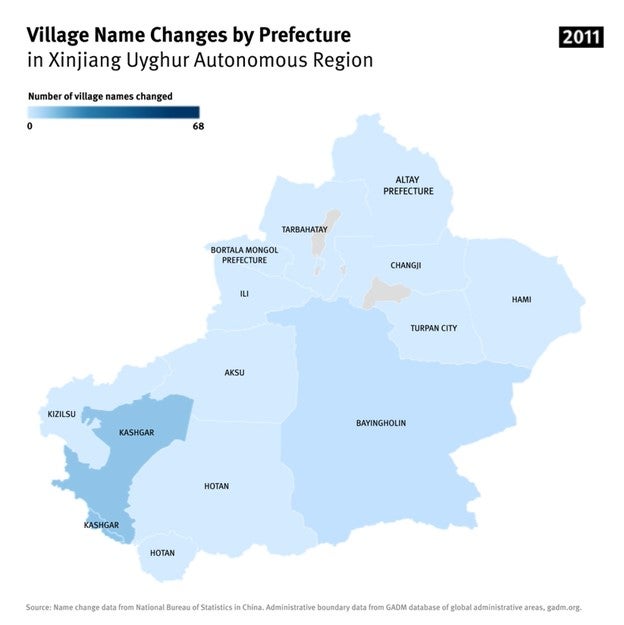

While the renaming of villages appears ongoing, most of these changes occurred between 2017 and 2019, when the Chinese government’s crimes against humanity escalated in the region, and mostly in Kashgar, Aksu, and Hotan prefectures, Uyghur majority regions in southern Xinjiang.

Because of a lack of access to Xinjiang, the full impact of the village name changes on people’s lives is unclear. Uyghur Hjelp interviewed 11 Uyghurs who lived in villages whose names had been changed, and found that the experience had a deep impact on them. One villager faced difficulties going home after being released from a re-education camp because the ticketing system no longer included the name she knew. She later faced more difficulties registering for government services due to the change. Another villager said he wrote a poem and commissioned a song to commemorate all the lost locations around where he had lived.

Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which China has signed but not ratified, states that, “In those States in which ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities exist, persons belonging to such minorities shall not be denied the right, in community with the other members of their group, to enjoy their own culture, to profess and practice their own religion, or to use their own language.”

The United Nations Human Rights Committee, the independent expert body that interprets the covenant, has stated in a General Comment that, “[t]he protection of these rights is directed towards ensuring the survival and continued development of the cultural, religious and social identity of the minorities concerned, thus enriching the fabric of society as a whole…. [T]hese rights must be protected as such.”

In May 2014, the Chinese government launched the “Strike Hard Campaign against Violent Terrorism” in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Since 2017, the Chinese government has carried out a widespread and systematic attack against Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims in Xinjiang. It includes mass arbitrary detention, torture, enforced disappearances, mass surveillance, cultural and religious persecution, separation of families, forced labor, sexual violence, and violations of reproductive rights. Human Rights Watch in 2021 concluded that these violations constituted crimes against humanity.

The Chinese government has continued to conflate Uyghurs’ everyday religious and cultural practices, and their expressions of identity, with violent extremism to justify violations against them. In April 2017, the Chinese government promulgated the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region Regulation on De-extremification, which prohibits “the propagation of religious fervor with abnormal ... names.” Authorities reportedly banned dozens of personal names with religious connotations common to Muslims around the world, such as Saddam and Medina, on the basis that they could “exaggerate religious fervor.”

In August 2022, the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) issued a report concluding that Chinese government abuses in Xinjiang “may constitute international crimes, in particular crimes against humanity.” While foreign governments have condemned Beijing’s policies in Xinjiang, and some have imposed targeted and other sanctions on Chinese government officials, agencies, and companies implicated in rights violations, these responses have fallen short of the gravity of Beijing’s abuses, Human Rights Watch said.

“Concerned governments and the UN human rights office should intensify their efforts to hold the Chinese government accountable for their abuses in the Uyghur region,” said Abduweli Ayub, founder of Uyghur Hjelp, “They should make use of the upcoming UN Human Rights Council sessions and all high-level bilateral meetings to press Beijing to free the hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs still wrongfully imprisoned as part of its abusive Strike Hard Campaign.”

For more details about the village name changes, please see below.

Examples of Village Name Changes

- In Kashgar Prefecture, Qutpidin Mazar village (库普丁麻扎村), named after a shrine of the 13th century Persian polymath and poet, Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi, was renamed Rose Flower village (玫瑰花村) in 2018;

- In Akto County, Kizilsu Kyrgyz Autonomous Prefecture, Aq Meschit (“white mosque”) village (阿克美其特村) was renamed Unity village (团结村) in 2018;

- In Aksu Prefecture, Hoja Eriq (“Sufi teacher’s creek”) village (霍加艾日克村), was renamed Willow village (柳树村) in 2018;

- In Karakax County, Dutar village (都塔尔村), named after a Uyghur musical instrument, was renamed Red Flag village (红旗村) in 2022.

A full list of these village names is available upon request.

Methodology

The National Bureau of Statistics of China publishes a list of “Administrative Division Codes for Statistics,” (统计用区划代码) in which each village is represented by a 12-digit code. These digits identify villages by the five administrative levels of China: province, city/prefecture, county, township, and village. In total, we were able to identify 25,394 unique Administrative Division Codes in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) between 2009 and 2023 (the exact number fluctuates each year). Of these, 23,291 are villages.

To simplify the process of identifying those villages with changed names, we first removed the suffixes of the village names that simply denote “village,” given that they may appear in different variations, such as “农业村” (farming village) and “牧业村” (herding village).

We found 3,652 village names that had been changed between 2009 to 2023. About 1,254 of them involve name changes in Mandarin Chinese (the village names changed, but both the name before and the one after are in Mandarin Chinese). The bulk of Chinese-to-Chinese name changes involve mundane changes such as from “First Company” to “Third Company” of the Sixth Division of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps.

Since the Uyghur language does not have a standard transliteration scheme to Mandarin Chinese, many villages use different Chinese transliteration from year to year. Human Rights Watch used “edit distance” – an algorithm that computes the similarities between names before and after the change – and removed the ones that are different Chinese transliterations of the same Uyghur name.

The remaining name changes – about 1,000 – mostly involve changes from Uyghur to Chinese, though in some cases, both the before and after names are both in Uyghur, and a few changed from Mandarin Chinese to Uyghur. Among these 1,000, about 350 involve similarly benign changes, such as from Qumchi Östeng (“sandy canal”) village to Jigdelik (“a place with date trees”) village.

But about 630 of the name changes involve changes that remove a religious, historical, or Uyghur cultural term and replaces it with a name that is generic or one that fits the Chinese Communist Party’s ideology.

Analysis of Data

Certain words are more likely to be removed from a village name. In 2009, there were 47 villages in Xinjiang with the word “mazar” (shrine) in their names; all but 6 villages have removed the word from their names. “Hoja” (religious teacher) appeared in the names of 28 villages in 2016, but only 3 remained by 2023. Ten of thirteen villages in Xinjiang that had the word “haniqa” in them, which means a Sufi meeting house, had renamed them. There are now no more villages with the word “xelpe” or “khalifa” (ruler) in their names.

Table 1: Village name changes by specific word

Name | Meaning | Number of changes | Percentage of change |

麻扎/Mazar | Shrine/Tomb | -41 | -88% |

霍加/Hoja | A Sufi teacher | -25 | -89% |

美其特/Meschit | Mosque | -17 | -100% |

哈尼喀/Haniqa | Or khanqah in Persian or Arabic, which means “a Sufi meeting house” | -10 | -92% |

拱拜孜/Gombez | Dome | -9 | -92% |

欧尔达/Orda | Palace | -9 | -100% |

海利派/Xelpe | Or Khalifa in Arabic, which means “ruler” | -7 | -100% |

瓦普/Wap | Islamic Foundation | -6 | -78% |

阿吉/Hajj | Pilgrimage | -6 | -67% |

苏里坦/Sultan | Sultan | -6 | -100% |

“Happiness” (幸福), 69 more named “Unity” (团结), 55 more named “Harmony” (和谐), 38 more named “Bostan,” which is “oasis” in Uyghur, and 38 more named “Light” (光明). For example, in Aksu Prefecture, Xelpe Eriq village, which means “Ruler Creek” in Uyghur, was renamed “Unity New village” in 2017. Mazar Östeng village, which means “Shrine Canal village” in Uyghur in Hotan Prefecture, has been “Bright Light village” since 2020.

Table 2: Most common replacement terms in village names

Name | Meaning | Number of changes | Percentage of changes |

幸福 / Xingfu | Happiness | +79 | +75% |

团结 / Tuanjie | Unity | +69 | +55% |

和谐 /Hexie | Harmony | +55 | +98% |

博斯坦 / Bostan | Bostan/ Oasis | +38 | +37% |

光明 / Guangming | Light | +38 | +72% |

友谊 / Youyi | Friendship | +26 | +72% |

红旗 / Hongqi | Red Flag | +23 | +82% |

红星/ Hongxing | Red Star | +17 | +78% |

前进/Qianjin | Forward | +17 | +60% |