- Ethiopian armed forces summarily executed scores of civilians in Merawi, a town in the Amhara region in late January and February amid fighting with Fano militia.

- Since armed conflict broke out in Amhara in August 2023, federal forces have committed numerous abuses with impunity.

- The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights should launch an independent inquiry into abuses in Amhara, and the UN and AU should consider suspending new deployments of Ethiopian forces from peacekeeping operations.

(Nairobi) – The Ethiopian military summarily executed several dozen civilians and committed other war crimes on January 29, 2024, in the town of Merawi in Ethiopia’s northwestern Amhara region, Human Rights Watch said today. The incident was among the deadliest for civilians during the fighting between Ethiopian federal forces and Fano militia since the outbreak of fighting in Amhara in August 2023.

The United Nations and African Union should consider suspending new deployments of Ethiopian federal forces into international peacekeeping operations until commanders responsible for grave abuses are held accountable.

“The Ethiopian armed forces’ brutal killings of civilians in Amhara undercut government claims that it’s trying to bring law and order to the region,” said Laetitia Bader, deputy Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “Since fighting began between federal forces and the Fano militia, civilians are once again bearing the brunt of an abusive army operating with impunity.”

Early in the morning of January 29, Fano forces attacked a contingent of Ethiopian soldiers in Merawi, about 30 kilometers south of the Amhara regional capital, Bahir Dar. The Fano fighters then withdrew, leaving the town to the Ethiopian federal forces. During a six-hour period, Ethiopian soldiers shot civilians on the streets and during house-to-house searches. Scores were killed, mostly men, but also women. The soldiers also pillaged and destroyed civilian property.

On February 24, Ethiopian armed forces summarily executed up to eight civilians in Merawi following another attack by Fano fighters in the town.

Between February 9 and March 14, Human Rights Watch interviewed 20 people by phone, including victims, their family members, and witnesses. Human Rights Watch also analyzed and verified two videos posted to social media in the aftermath of the January 29 attack, and examined satellite imagery that corroborated witness accounts. On March 5, Human Rights Watch provided a summary of its preliminary findings to the Ethiopian government, but received no response.

On January 29, a 26-year-old woman was at home in Merawi with her husband and infant son when the fighting broke out. Once the battle ended, they peered out their door to see what was going on. “Three soldiers and two police officers came out of nowhere,” she said. “My husband was carrying our 2-month-old child. They told him to let our child go, and after he did, they shot him right outside the house. After they shot him, they did the same thing to the neighbor.”

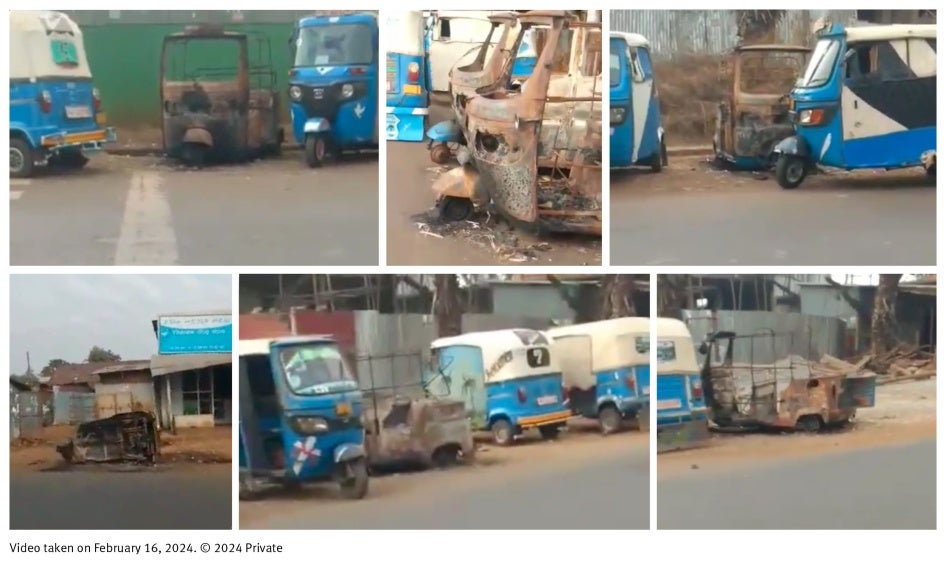

Residents said soldiers looted homes, hotels, and businesses, and burned at least 12 Bajaj motorized three-wheel vehicles.

Human Rights Watch was unable to determine the total number of civilian deaths in Merawi. Community leaders shared two lists of victims with a total of forty names of people who were identified and buried in Merawi. Three residents estimated that over eighty people were killed, including some buried elsewhere.

Human Rights Watch verified and analyzed a video recorded on January 30 showing at least 22 bodies lining the main road in Merawi. Ethiopian forces refused to allow the community to collect the dead until later that morning.

The nongovernmental organization, the Ethiopian Human Rights Council, found that 89 civilians had been killed in Merawi. Initial findings by the national Ethiopian Human Rights Commission, a federal state body, concluded that Ethiopian forces killed 45 residents.

Under international humanitarian law applicable to the armed conflict in Amhara, the deliberate killing or mistreatment of civilians, and looting and pillage of civilian property are prohibited and may be prosecuted as war crimes.

An Ethiopian government spokesman told the media that Fano fighters attacked an army base in Merawi but maintained that the military only acted in “self-defense,” including when searching houses, and did not target civilians. Residents said that Ethiopian soldiers called a meeting on February 12 and only acknowledged that four civilians had been killed and that they burned one Bajaj.

Ethiopia’s international partners, including the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom, issued statements condemning the massacre of civilians and calling for an independent investigation. Since the end of the UN-mandated inquiry on Ethiopia in October 2023, there has been little international monitoring of the human rights situation in the country.

Concerned governments should press for resumed scrutiny of human rights in Ethiopia at the UN Human Rights Council, and call on the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to urgently investigate and publicly report on abuses in Amhara, including in Merawi, and other conflict-affected areas, Human Rights Watch said. The EU should clarify that reengagement with Ethiopia is intended to result in concrete measures by Ethiopian authorities to prevent further abuses against civilians, including by allowing independent investigations into the Merawi killings, and holding those responsible for abuses to account.

In June 2023, the US government determined that Ethiopia was “no longer engaging in a pattern of gross human rights violations.” Given reports of grave abuses by Ethiopian government forces, the US in its engagement with the Ethiopian government should prioritize protecting civilians and addressing justice and accountability issues.

The UN Department of Peace Operations and the AU Peace and Security Council should consider suspending any new deployment of Ethiopian soldiers from peacekeeping missions, Human Rights Watch said. Ethiopia has been one of the continent’s largest contributors to peacekeeping forces. The UN requires governments, alongside the UN, to ensure their nationals serving with UN peacekeeping missions have not committed past abuses, although such screening is usually left to national bodies. The AU is also putting a screening process in place.

The Ethiopian government’s failure to ensure meaningful accountability for abuses by federal and regional forces contributes to ongoing cycles of violence and impunity.

“The deliberate mass killings of civilians by Ethiopian government forces have sadly become a feature of daily life for countless Ethiopians in conflict areas,” Bader said. “Ethiopia’s partners, the African Union, and the UN should take concrete steps to end the impunity that abusive Ethiopian commanders have long enjoyed.”

For background information and further accounts of the conflict in Amhara, see below.

Armed Conflict in Amhara

In April 2023, after the government announced plans to dismantle regional special forces in the country and formally integrate them into the military, police, or regional police forces, Fano militias and the Ethiopian military clashed in towns throughout the region. The fighting intensified, and in August 2023, Fano attacked and captured major cities in Amhara. In response, the federal government declared a six-month state of emergency and placed the Amhara region under a military command post accountable to the prime minister. On February 2, 2024, Ethiopia’s parliament extended the state of emergency for another four months.

The United Nations, human rights groups and the media have reported on security forces abuses’ in Amhara, including the summary killings of civilians, unlawful drone strikes, and mass arrests without due process. Human Rights Watch received reports that armed groups have looted homes, imposed “taxes” on civilians, and abducted people they suspect of supporting the government. Ethiopian authorities have accused Fano of assassinating senior regional security officials.

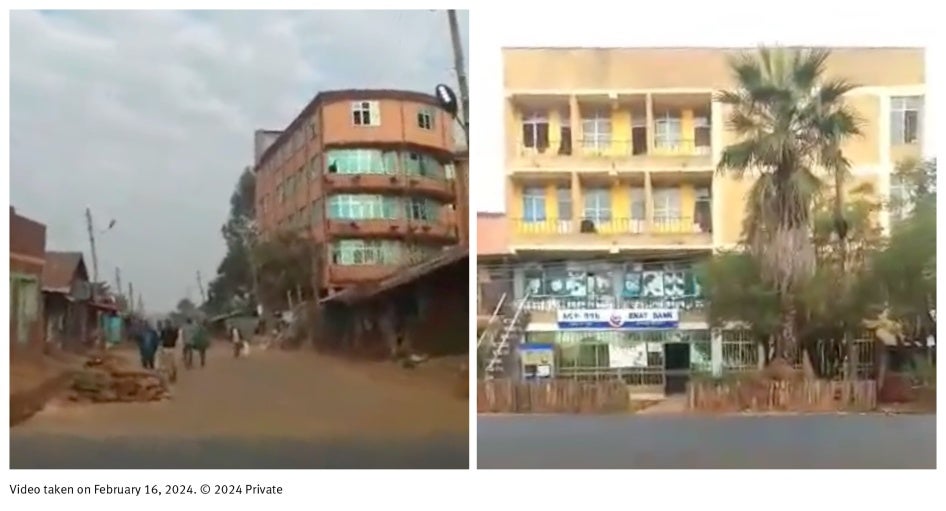

In September, the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission reported that government security forces carried out abuses in Merawi, a town of 35,000 people in North Gojjam Zone, Amhara. It is along the A3 road, 30 kilometers southwest of Bahir Dar, the regional capital. “This town is bigger than the villages around it, so many people come here for work, to do business, and visit family,” a Merawi businessman said. Other residents said that farmers and daily laborers also go to Merawi for work.

Since August, control of Merawi has shifted multiple times between Fano and the Ethiopian military. One resident said: “Merawi used to be a comfortable place to live … everyone could work freely. Now, people’s lives are in danger, our lives are valued less than chickens. … We hear gunshots every day. You don’t know whether you will be killed or wake up the next day.”

Fighting in Merawi

Early in the morning of January 29, Fano fighters entered Merawi and attacked Ethiopian soldiers who had deployed in the town’s administrative office. The office, in the Kebele 02 neighborhood, lies just off the main road that cuts through the town, and is near homes, businesses, and banks. A Bajaj stand is 175 meters northeast of the office.

Sounds of gunfire erupted in Kebele 02 at about 6:30 a.m., with Ethiopian forces returning fire. One business owner awoke to the sounds of shooting: “Fano encircled the admin building.… They were trying to get on top of Hibret Bank, which was under construction.… When the Fano would shoot, the soldiers would fire back … it was raining bullets.”

Residents sheltered in their homes, waiting for the clashes to end. The fighting lasted for hours, until around 11:30 a.m., at which point Fano forces withdrew from the town. Residents later said Ethiopian soldiers suffered heavy losses, and that at least two Fano fighters were also killed in the clashes.

Summary Execution of Civilians

From about noon until 6 p.m., the Ethiopian armed forces went on a killing spree against residents of Merawi.

After Fano forces withdrew, government reinforcements entered the town shortly after 11:30 a.m. from the direction of Dangla town, east of Merawi, two residents said.

“It got quiet after that,” said a nurse. “But after a while, I started hearing gunshots [again]. We noticed the shootings were only coming from one side, they weren’t returned. We then realized they [the soldiers] were going around shooting people.”

After the gunfire stopped, some residents tried to see what happened. Others, accustomed to repeated clashes in the town, tried to go to work. “After the Fano left, people went to the tela bet [a house serving home-brewed beer] to pack their lunch and go to work,” said a Bajaj driver who had been hiding in a tela bet in Kebele 02 since the fighting started. “But soldiers came in.… They accused the people of being Fano, saying, ‘You are just pretending to be civilians by mixing with the people.’ That is when they took several people.” The following day, the driver said he saw the bodies of at least 17 people lying on the street, including those who had been in the tela bet with him.

Residents described the horror of seeing soldiers moving through town and executing people. “I peeked through the window and saw soldiers going around on the main road to different places,” said a man who watched from his home off the main road. “I saw them drag someone out from their home and shoot them. My two kids were with me. I was worried they would eventually come too.… so, we went to hide.”

Five soldiers went to the house of a priest. “They told me to come out of my house,” said the priest. “I told them I didn’t know anything, that I only served the church. One of the soldiers finally said, ‘We are here to kill the enemy, not someone like him.’ So, they left for other houses.”

The priest later called to check on a relative, a 52-year-old father of five: “A soldier picked up instead and said, ‘He is here; you can come take the body.’ They hung up. The next time I called, the phone was off.” His relative had been killed.

The 26-year-old woman who witnessed soldiers shoot her husband and her neighbor said that the soldiers also prevented her from mourning her loss. They interrogated her and the other female residents in the compound for an hour. She said:

They asked ‘Who are the Fano? Where are they?’ We kept telling them we didn’t know. My 2-month-old was crying, because he fell on the floor when my husband let him go. While he was questioning me, I was trying to calm the baby down. The soldier turned to the baby and asked me if it was a boy. I said yes. He then pointed the gun at the baby. I was begging and crying, asking him to leave us and spare the baby. He finally left us alone. I wanted to pick the bodies up, but the soldiers refused and said we shouldn’t cry.

She said that the soldiers remained for one hour, leaving the bodies in the sun:

[My husband] was such a good man. Seeing him lying there, I hated being alive. When they aimed the gun at my child. I couldn’t believe it. How could you consider a child, one so small, the enemy?

One resident saw soldiers drag a priest, Qes Yitayih, and two other men, Misganaw Amare, a tailor, and Habtam Embyale, a university student, from their homes. He later saw their bodies on the street: “It seemed they were targeting men that day.” Another resident witnessed soldiers pull out Qes Yitayih and three other residents, including a day laborer named Tesfa Endalew, from a compound and execute them. He said:

Five soldiers went to the compound, a lot more were outside and on guard. I didn’t recognize them, I just know they were part of the military. They pulled four men out, including Qes Yitayih, made them kneel down, and shot them in their foreheads. Once I saw that, I left and went to hide.

Human Rights Watch verified a 39-second video that appeared on social media platforms in early February. The video, made up of two clips filmed from inside a vehicle traveling slowly during daylight at an undetermined time, shows about 200 meters of the main road in Merawi. Human Rights Watch counted at least 22 bodies, 15 of them clearly male. None of the bodies that Human Rights Watch can clearly distinguish appear to be wearing uniforms or shoes typical of Fano militia, and no weapons are visible. Many are without shoes. Blood marks the road next to at least 10 bodies from wounds near the heads, indicating that they were shot in the head, and possibly executed in the same location. Some of the heads have been covered with clothing. At least four bodies lie next to each other on the roadside.

Most of those killed appeared to be men, but some of the victims were women. One man said he received a phone call from a resident urging him to check on his relative who lived in Kebele 01. He said:

She lived along the road, selling vegetables, a few houses away from us. When we got there, she was lying on the floor, dead, with her child on top of her crying. When we tried to take her, we saw soldiers, and were scared, so we took the child, and left her. After a while, we went back, avoiding the main road, to take her body to her father’s house.

Looting and Destruction of Property

The soldiers carrying out killings also looted and damaged homes and businesses leaving a terrible impact on daily life.

One woman said the soldiers pillaged the bodies of those executed as well as people’s homes:

The [soldiers] locked us in one room. By the time we were let out, everything was a mess. They went through our houses. They took valuable items, money, from my neighbor’s house. They even emptied cash and phones from the pockets of my dead neighbors.

One resident said he saw soldiers repeatedly entering the Tinsae Hotel, on the main road in Kebele 02, to steal food, beer, and equipment:

They would cut up meat and fill up plastic bags, maybe two to three kilograms of meat each, take six beers, and leave. Then another group would come and do the same. They were doing this in turns, for hours.... They tried to open the beer draft machine, but couldn’t, so they shot it up… They took the Wi-Fi equipment; the generator was gone. Everything was gone.

Several residents said soldiers burned 12 Bajaj three-wheelers in the aftermath of the fighting. Human Rights Watch received an additional 2:06 minute video from a journalist, Zecharias Zelalem, which was reportedly filmed on February 16. The video, made up of at least eight clips, shows at least six destroyed Bajajs and damage to the windows of the administrative building.

A driver, whose Bajaj was burned by soldiers, said: “Today is the 17th day I am just sitting in the house. I no longer have a job , because they [the soldiers] burned my Bajaj. I don’t have an income anymore. I have no purpose anymore. If I can’t work, what options do I have? The men can’t live in peace.”

Burials, January 30

The following day was an Orthodox religious holiday, the commemoration of the death of Mary. Residents who ventured out of their homes early that morning to go to church found bodies lying in the town’s main road.

Several residents said that soldiers remaining in the town refused to allow the community to collect and bury the dead.

A teacher said: “The next day up to 9:30 a.m., they were not allowing people to take bodies. You would see mothers and wives of people killed staring at their loved ones, unable to do anything. Sad, but they weren’t allowed to cry or mourn.”

One man learned of the loss of his friend, Tamerat, who was killed outside his butcher shop. Two residents said that soldiers ate meat from Tamerat’s shop after killing him.

Another resident said that when he attempted to recover the body of his brother, soldiers fired at him: “The soldiers said, ‘Are you trying to take the Fano body? You are the family of Fano.’ I said no, he is not Fano, he is a civilian, can’t you see what he is wearing? You can tell he is a civilian. They said that we kept giving excuses and shot in our direction.”

A priest leading prayers at the Mariam church said that a group of elders were sent to negotiate with the military, who finally allowed the residents to collect the dead after 9 a.m. One resident said that soldiers separated the bodies of those they believed were two Fano fighters based on their uniforms, but allowed residents to pick up the other bodies.

Relatives and community members rushed to collect and bury the bodies. “We contributed money to help pick up and cover them,” said one Bajaj driver. “So, whoever lost their loved ones, would come and identify their person and take them.”

A priest said that the soldiers compelled people to bury the victims quickly, in mass graves, inconsistent with Orthodox funeral rites:

You are supposed to clean the body, pray for them.… But we were not allowed to do that for these people. People were buried with their bloodied clothes. We couldn’t cover the whole body with fabric. People mourning didn’t put up the tent afterwards [at their homes to receive mourners], no one could come grieve. The soldiers said if you put up a tent, we will kill you. The families were forced to mourn behind closed doors.

Victims were buried in at least three mass graves in the church compound, taken to rural areas, or to their ancestral homes. The bodies of three Muslims were buried in the Muslim graveyard on the outskirts of town.

Satellite imagery recorded on February 8 shows new possible graves on the southern part of the church compound.

Ongoing Abuses

Residents who could afford to leave Merawi fled to Bahir Dar, Addis Ababa, or other cities. “Everyone has left the town, including me,” said a Merawi resident in late February. “I was there yesterday, but it is so empty. Almost everyone has left. The ones that are still there are moving with no hope. You can see it. You feel something in the air. People have given up. They have seen what these soldiers can do. They are just waiting for their day.”

Residents who remained behind spoke of continued fear and abuses as Ethiopian forces remained in control of Merawi town in the aftermath of the massacre. Several residents said that on February 12, the military called a town meeting. One participant said soldiers forced residents to attend:

All the [soldiers] did was deny everything. They denied what people saw with their own eyes. The [soldiers] said people killed were part of the war. They admitted to only killing four civilians and damaging one Bajaj. They claimed they would compensate for this. They urged people start working again, and that if the people want Fano to lead, they can change the war to one using jet airplanes instead of foot soldiers.

Residents said that on February 24, Fano fighters again attacked Ethiopian forces in the town, bringing further reprisals by government forces. A man whose house is near the outskirts of town heard gunfire until around 3 p.m., when he saw Fano fighters leaving.

Human Rights Watch confirmed that government soldiers killed at least two civilians that day and possibly as many as eight.

A 49-year-old resident said that he found the body of his son in Bahre Timket field, alongside the bodies of seven other people, outside their home that evening:

My son and a neighbor’s kid wanted to go to the field outside our home. I warned him not to go, because of what happened last [month]. But he said the shooting was done and [he] needed some air. It was just 10 meters away, so I thought to let him go. Shortly after, I heard gunshots, and a neighbor told me he’d been shot. I didn’t know what to do, so I called his phone. A man picked up.… I think it was the soldier that killed him. He said hello, hello, twice and hung up. My son wasn’t armed, he was wearing flip flops. They could tell my son wasn’t involved in this, but he was shot. He was 23, he was leaving for university the next day. I wish I didn’t let him go to the field so he would live another day.

A 55-year-old resident said that government soldiers began beating people they came across on the road in Kebele 01. Later that evening, he found his son’s body in the field outside their home:

After the Ethiopian military left, we waited until 8 p.m. to check on them and collect the bodies. Some were missing phones, shoes. One of the victims was my son. I only have one child – my son – no one else.