Summary

In December 2016, Gambians will go to the polls to vote for a president for the fifth time since current leader Yahya Jammeh came to power in a 1994 coup. Over the past 22 years, President Jammeh and the Gambian security forces have used enforced disappearances, torture, intimidation, and arbitrary arrests to suppress dissent and preserve Jammeh’s grip on power. Ahead of this year’s election, the government has repeated these tactics, with a crackdown on opposition parties, particularly the United Democratic Party (UDP), that has all but extinguished hopes for a free and fair election.

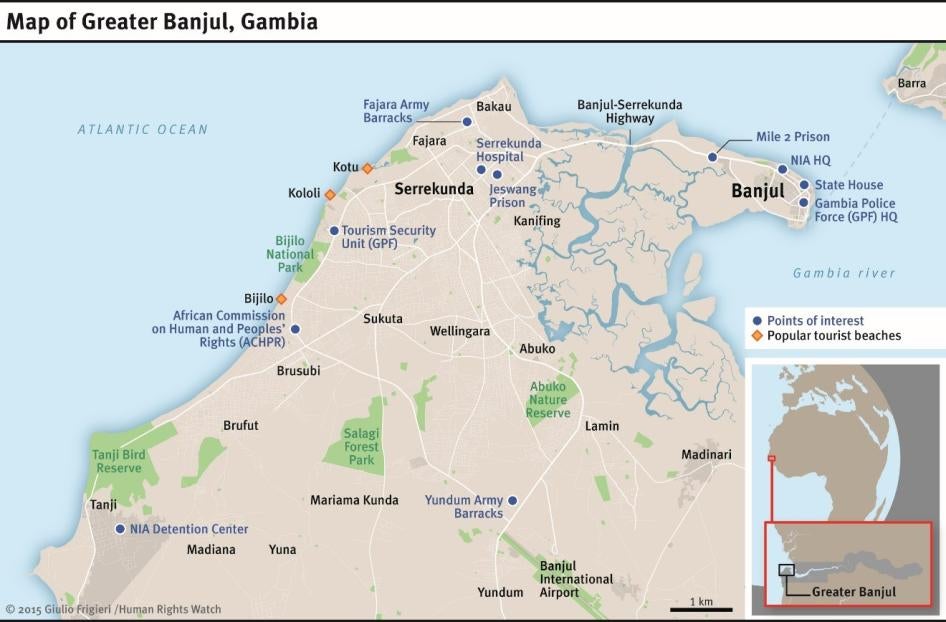

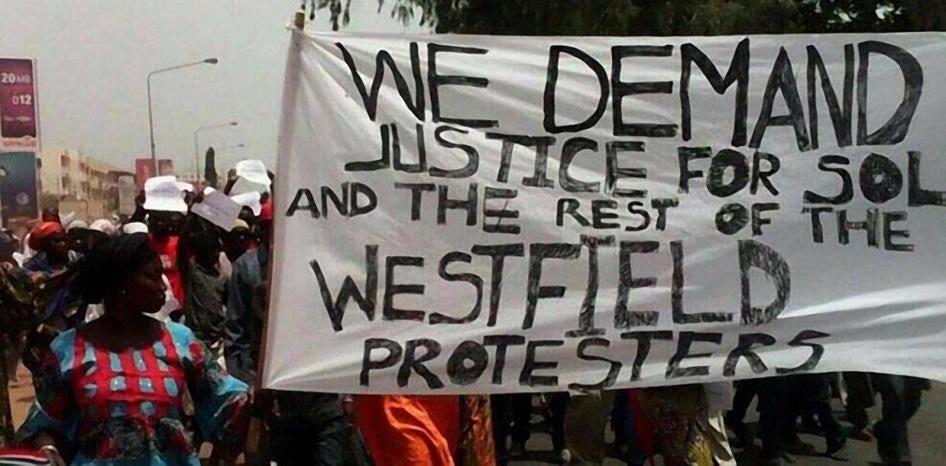

The government’s crackdown began on April 14, when prominent UDP activist Solo Sandeng led a rare public protest calling for electoral reform. He was arrested by Gambian police, taken to the headquarters of the National Intelligence Agency (NIA), and brutally beaten to death. Many protesters arrested with Sandeng were also tortured at the NIA; several were beaten and doused in water while being forced to lie on a table.

Gambian authorities have in 2016 arrested more than 90 opposition activists, including those arrested with Sandeng, for participating in largely peaceful protests. Courts have convicted 30 opposition members and sentenced them to three-year terms, including UDP leader Ousainou Darboe and many of the UDP leadership. Jammeh has also repeatedly threatened opposition parties. “Let me warn those evil vermin called opposition,” he said in May. “If you want to destabilize this country, I will bury you nine-feet deep.”[1]

Based on more than 100 interviews conducted in Gambia, Senegal, and the United States from March to September 2016, this report examines the chilling effect of the government’s targeting of political opponents, journalists, and other dissenting voices on the ability of opposition parties to contest elections on a level playing field. Human Rights Watch interviewed members of political parties, journalists, civil society leaders, lawyers, retired Gambian civil servants, former members of the security forces, international organizations, and foreign diplomats.

The abuses committed since April, as well as Jammeh’s repeated threats, have reinforced a climate of fear among many opposition politicians and activists that severely limits their ability to criticize Jammeh and his government.

Even those parties able to operate relatively freely told Human Rights Watch that they believe their opposition to the government puts them at risk of arrest. They worried that if they become too great a threat to Jammeh’s chance of winning the election, they too will be targeted.

Opposition parties are also constrained by the legally mandated two-week official election campaign, the only time opposition parties receive any significant coverage on state radio and television. Although Gambia has numerous private newspapers and radio stations, many critical journalists temper their reporting of the government to avoid reprisals.[2] The short campaign period, coupled with the government’s near-monopoly of state media at other times, makes it extremely difficult for opposition parties to engage meaningfully with potential voters.

President Jammeh and the ruling Alliance for Patriotic Re-Orientation and Construction (APRC) have also routinely used state resources for campaigning, including government vehicles and buildings, and have mobilized civil servants and security force members to act on behalf of his reelection. Before campaigning even begins, Jammeh has exploited his nationwide and constitutionally mandated “Meet the People” tour to promote his candidacy.

The quality of elections, however, depends on more than simply how the polling day is conducted. The government’s intimidation of journalists and opposition leaders and supporters, its domination of state media, and its use of state resources for campaigning give the ruling party a clear advantage over other parties.

International human rights law provides important protections that the Jammeh government has frequently violated, including the rights to security of the person, to a fair trial, and to freedom of expression, association, and peaceful assembly. Article 25 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which Gambia has ratified, guarantees the right “of every citizen to take part in the conduct of public affairs, the right to vote and to be elected and the right to have access to public service.”

In 2001, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) adopted the Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance (ECOWAS Protocol), which includes specific provisions promoting democratic elections. The ECOWAS Protocol provides that political parties should “have the right to carry out their activities freely, within the limits of the law” and “without hindrance or discrimination in any electoral process. The freedom of the opposition shall be guaranteed.”[3] The Protocol also requires that all parties can meet and organize peaceful demonstrations in advance of elections while “[t]he armed forces and police shall be non-partisan and shall remain loyal to the nation.”[4]

The Gambian government should immediately release all peaceful protesters being held, initiate a transparent and impartial investigation into opposition deaths in custody, grant opposition parties access to state media outside the framework of the official campaign, and cease using state resources for campaigning. The government should also ensure that the security forces respect the opposition’s rights to freely and peacefully campaign without fear of harassment or arrest.

Gambia’s key international interlocutors, including ECOWAS, the European Union, and the United States, have been robust critics of the government’s crackdown. But they have not sufficiently demonstrated to President Jammeh that his persistent targeting and intimidation of opponents has tangible consequences. They should set clear benchmarks for the government to meet ahead of the election and, if it fails to do so, ECOWAS should suspend Gambia from its decision-making bodies, and the US and the EU should impose travel bans, asset freezes and other targeted sanctions on senior officials implicated in human rights violations.

Methodology

This report is based on more than 100 interviews conducted in Gambia, Senegal, and the United States from March to September 2016. Human Rights Watch interviewed, among others, members of six political parties, journalists, civil society leaders, lawyers, retired Gambian civil servants, former members of the Gambian security services, representatives from international organizations, and diplomats.

Most interviews were conducted in English. In exceptional cases where interviewees were more comfortable in other languages, their family members acted as interpreters. Interviews were mostly conducted individually, although some group interviews were organized where participants preferred to be interviewed in groups and where there was no identifiable risk of putting anyone at risk of reprisal. For security reasons, many interviews were conducted over the phone using secure communications. No compensation, aside from modest travel expenses for Gambian refugees in Senegal, was given to any person interviewed.

Many interviewees feared for their or their family’s well-being if the Gambian government became aware that they were interviewed by Human Rights Watch, and asked that their names be withheld. We have complied with these requests and intentionally omitted identifying details of the vast majority of individuals who met a researcher.

Human Rights Watch provided a summary of findings and a list of questions to the Gambian Minister of Information and the Gambian Ambassador to the United States on October 19. No response was received at the time of writing.

Abbreviations

|

APRC |

Alliance for Patriotic Re-Orientation and Construction |

|

DPP |

Director of Public Prosecutions |

|

ECOWAS |

Economic Community of West African States |

|

GDC |

Gambia Democratic Congress |

|

GRTS |

Gambia Radio and Television Services |

|

IEC |

Independent Election Commission |

|

NIA |

National Intelligence Agency |

|

PIU |

Police Intervention Unit |

|

UDP |

United Democratic Party |

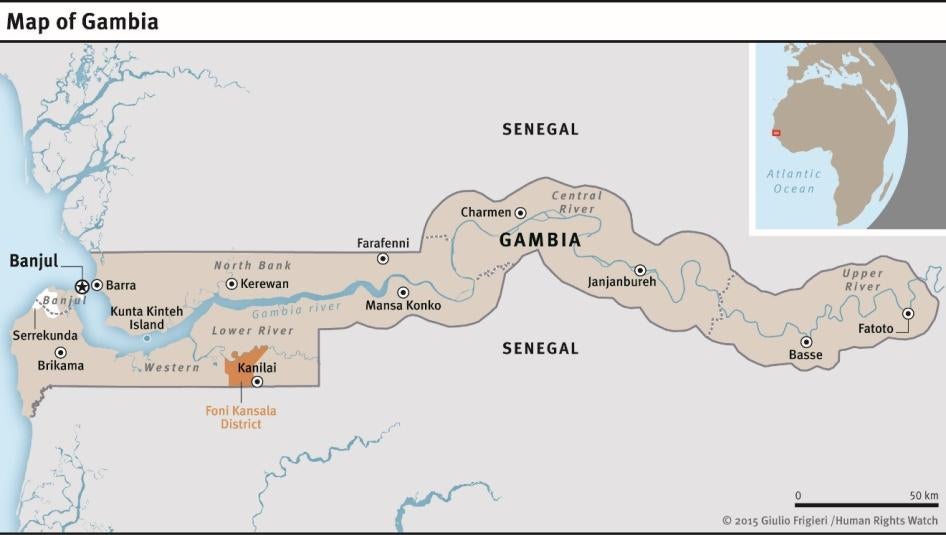

I. Background: A History of Flawed Elections

President Yahya Jammeh seized power from Dawda Jawara, the country’s post-independence leader, in a coup on July 22, 1994. Although he initially promised to step aside after three months to allow democratic elections to take place, Jammeh has now ruled for more than two decades. He was first elected president in a widely criticized 1996 election, characterized by intimidation and violence, in which the main opposition parties were banned from participating.[5] He has since been reelected a further three times, and he has developed a long track record of using the machinery of the state, particularly the security forces, to intimidate and suppress the opposition in advance of elections.

The 2001 and 2006 presidential elections – the first in which the main opposition parties were allowed to participate – were deemed “relatively free and fair” by the United Nations, but UN officials in October 2006 expressed concern about the dearth of independent media and lack of robust political opposition.[6] Several independent journalists were killed, forcibly disappeared or tortured between 2004 and 2006,[7] and at least three United Democratic Party (UDP) supporters were arrested prior to or soon after the 2006 presidential elections, reportedly for their political activism.[8] One of them, Kanyiba Kanyi, is still missing.[9]

Prior to the November 2011 presidential elections, ECOWAS stated that its pre-election assessment mission “paints a picture of intimidation, an unacceptable level of control of the electronic media by the party in power, the lack of neutrality of state and parastatal institutions, and an opposition and electorate cowed by repression and intimidation.”[10] In March 2011, two family members of exiled opposition leader Mai Fatty were arrested and detained for displaying political campaign materials. Amadou Scattred Janneh, a former minister of information, was detained incommunicado for a week at a secret detention center in June 2011, after printing 100 t-shirts emblazoned with the slogan “End to Dictatorship Now.”

Following the 2011 elections, the government continued to target opposition activists. In December 2013, Amadou Sanneh, the national treasurer of the UDP, and two other UDP members, Alhagie Sambou Fatty and Malang Fatty, were convicted of sedition and sentenced to five years’ imprisonment.[11] In December 2013, UDP National Organizing Secretary Solo Sandeng was detained for almost a month, including 10 days incommunicado at the NIA, for allegedly organizing an unlawful protest.[12] In April 2015, Gambian security forces erected roadblocks at Fass Njaga Choi in the North Bank Region to stop a UDP nationwide tour that had been denied a permit. The UDP leadership remained stranded for four days until a permit was issued and the tour could proceed.[13]

In July 2015, Gambia’s National Assembly adopted an amendment to the elections laws that opposition parties criticized as an effort to restrict opposition participation in the upcoming 2016 presidential and 2017 parliamentary elections.[14] The Election (Amendment) Act 2015, they said, imposed prohibitive conditions on presidential candidates and their parties to be registered by the Independent Election Commission (IEC), notably by sharply increasing the deposit needed to run for president from 10,000 Dalasi (approximately US$230) to 500,000 Dalasi (approximately $11,830), requiring a party’s executive members to be resident in Gambia, and requiring parties to maintain a secretariat in each of Gambia’s five regions.[15]

Ultimately, however, the IEC registered eight parties, including the ruling Alliance for Patriotic Re-Orientation and Construction (APRC) and the UDP, the opposition party that won the largest share of the opposition vote in the 2006 and 2011 presidential elections.[16] A ninth party, the Gambia Democratic Congress (GDC), was registered on May 18, 2016.[17] At time of writing, seven opposition parties were in discussions about the formation of a coalition that would support a single candidate in the December elections.

Despite concerns over the 2015 Elections (Amendment) Act, several diplomats told Human Rights Watch in January 2015 that the renewed willingness of the Gambian authorities to grant permits for opposition rallies in late 2015 and early 2016 suggested that the government might be open to a more genuine dialogue on electoral reform prior to the 2016 presidential elections.[18] “It was a much more hopeful picture before April 2016,” one diplomat later told Human Rights Watch. The calculus changed, however, when the April death in custody of Solo Sandeng demonstrated the Gambian government’s tendency to again resort to violence and intimidation to suppress political opposition.

II. Response to Peaceful Protests

Death of Solo Sandeng

On April 14, more than 25 opposition activists, including UDP National Organizing Secretary Solo Sandeng, marched in Serrekunda, a suburb of Banjul, holding banners calling for electoral reform. Aminata Sandeng, Sandeng’s daughter, told Human Rights Watch, “When our father went out, it was because he was frustrated that the current election environment isn’t favorable to opposition parties.”[19]

Members of Gambia’s Police Intervention Unit (PIU) descended on the protest and arrested Sandeng, more than 20 other demonstrators, and several bystanders. Initially detained at the PIU headquarters in Kanifing, Sandeng and at least four other protesters were taken to the headquarters of Gambia’s National Intelligence Agency (NIA) in Banjul, where detainees are often beaten and tortured.[20] More than 20 other protesters initially detained at Mile 2 prison were reportedly transferred to the NIA in the early hours of April 15.[21]

Sandeng did not survive his custody with the NIA. Nogoi Njie, a businesswoman arrested with Sandeng, stated in a sworn affidavit that Sandeng was heavily beaten while in detention. She said that, when she first saw Sandeng at the NIA, “They had already beaten him. His body was all swollen and [he was] in severe pain.”[22]

She described how she saw Sandeng lying on the ground next to a table where Njie herself was beaten and doused in water. “I saw then Solo lying on the Bahama grass next to the table flat on the ground badly beaten and bleeding profusely,” she stated.[23] “I shouted the name of God and called out to Solo. …He did not respond to my call. I then saw his head moving from side to side.” Later, after security personnel had beaten her with hose pipes and batons, she “again called out to Solo but he did not respond.”[24]

Many of the other April 14 protesters held at the NIA allege they were beaten and tortured, with several describing, like Njie, being forced to lie on a table and beaten while being doused in water. Seven protesters were hospitalized due to the injuries they sustained in custody.[25]

Fatoumatta Jawara, another female protester, stated in a sworn affidavit dated May 11 and publicly available that, while she was at the NIA, she was severely beaten. She stated: “They took me to one dark place. I could not tell where I was because my face was covered with my head tie. They undressed me and I was so seriously beaten I collapsed.”[26] Jawara said that she was beaten again after she acknowledged she was the female youth wing president of the UDP. “When they are beating you, they continuously pour water on you,” she said.[27] Human Rights Watch has had access to the statements of several other people arrested on April 14 who similarly described being beaten at the NIA and doused in water while forced to lie on a table.

Njie says in the affidavit that the men who beat her were dressed in black wearing a black hood and gloves, a description that matches the clothing often worn by the “Jungulers,” an unofficial security unit of up to 40 personnel, largely drawn from the Presidential Guard, that is frequently implicated in serious abuses.[28]

Eighteen people arrested on April 14 were eventually brought to court on April 20, charged with public order offenses and denied bail. The Gambian constitution requires that anyone arrested or detained should be brought to court within 72 hours.[29] The Gambian authorities failed to produce Ngoi Njie, Fatoumatta Jawara, Fatou Camara, and several other protesters on April 20, as all were still receiving treatment for their injuries. They appeared in court for the first time on May 4.[30]

Response to Sandeng’s Death

For weeks after Sandeng’s arrest, the Gambian government did not acknowledge his death or provide any explanation for his disappearance, despite calls for an investigation from the UN secretary-general,[31] the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights,[32] the European Union,[33] and the United States.[34]

Sandeng’s children told Human Rights Watch that the government’s failure to confirm their father’s death had worsened their grief. “As a family, when someone has died like that, when it is your dad, you still have hope,” said Fatoumatta, his daughter. “You can’t help it.”[35]

When asked about Sandeng’s death in a May 29 interview, President Jammeh acknowledged there had been a death in custody, without referring to Sandeng’s name, but he said:

“People die in custody or during interrogations, it's really common. This time, there is only one dead and they want investigations? No one can tell me what to do in my country.”[36]

It was not until June 22 that Saihou Omar Jeng, the NIA’s director of operations, explicitly acknowledged in a court affidavit that Sandeng was dead, saying that he “unfortunately lost his life in the whole process of arrest and detention.” He cited the causes of death as “shock” and “respiratory failure.”[37] A medical certificate attached to Jeng’s affidavit indicated the date and time of death as April 15 at 4:20 a.m.

The Gambian government has so far provided no further details of the circumstances of Sandeng’s death and has not returned his body to his family. “It’s really hard to grieve when you haven’t had a chance to see the body,” Sandeng’s wife told Human Rights Watch. “It makes you think, maybe they are still hiding him.”[38]

Arrest of the UDP Leadership

Upon learning of Sandeng’s death early on April 16, Ousainou Darboe, the UDP leader, marched with dozens of supporters from Darboe’s house toward the PIU headquarters where Sandeng had initially been detained, chanting, “Release Solo Sandeng, dead or alive.”

PIU officers arrived to stop the protesters from marching and, when they refused, beat them with batons and arrested more than 20 protesters, including Darboe. “As we walked, a paramilitary truck stopped in front us and started pushing us back,” one demonstrator told Human Rights Watch. “And from there, they started beating us with their batons, and arrested many of us.” He said that police eventually fired teargas to disperse the demonstrators.[39]

In a statement seen by Human Rights Watch, one of the protesters said he saw several demonstrators hit by batons after they were detained in the PIU truck, several of whom were bleeding profusely.[40] In other statements seen by Human Rights Watch, protesters reported being slapped by PIU officers while being transported from the site of the protest to the PIU headquarters in Kanifing.

Police officers sought to justify their use of force against demonstrators by saying that the protesters threw stones at them after they blocked the protesters from continuing their march.[41]

However, several protesters told Human Rights Watch that it was only when police began beating protesters that some started throwing stones. “When they started beating us, some people threw stones,” said one demonstrator. “That’s when they fired tear gas.”[42] Another said, “They kind of had us cornered, against a wall, and so people started throwing some stones, but only after we were being hit by the police, so we threw stones kind of to defend ourselves.”[43]

Nineteen protesters, including UDP leader Darboe and several UDP executive members, appeared in court on April 20, were charged with public order offenses and were denied bail.[44] They were held incommunicado from April 16 to 20, without access to legal counsel or family members. Many of those arrested on April 16 had noticeable injuries when they were brought to court.[45] Some 15 other protesters arrested on April 14 and 16 were released prior to the April 20 court appearance.[46]

Suppression of May 9 Protest

Following the arrests of the April 16 protesters, UDP members organized a rally on May 9 to mark a court appearance by Darboe and other demonstrators. Once again, Gambian police broke up the protest and beat protesters, including one woman who had given birth a few weeks earlier. The police arrested 45 people, including 6 women, initially detaining them at the PIU headquarters nearby.

“The police came out and said, ‘Nobody will pass,’” one demonstrator said. “We tried to keep going, but they fired teargas at us. I ran, and as I was running they hit me with a long piece of black pipe.” She said that after being taken to the PIU, she felt pain all over her body. “All I could think of was who would look after my kids,” she said.[47]

One man said that he was standing on the margins of the demonstration when police arrested him and took him to the PIU headquarters. “I tried to explain to the police officers that we weren’t even with the protesters,’” he said. “But one slapped me and said, ‘Don’t even try to explain.’”[48]

Several protesters said that once at the PIU, they saw the injuries other protesters had suffered. “There were lots of us in a big hall. Some people were bleeding from the head, others from the feet,” one said. “One person was so badly injured on his hand that he couldn’t hold anything.”[49]

On the night of May 9, the 39 male protesters were transported by bus to Janjanbureh prison, a five-hour drive from Banjul. During this journey several police officers told them that they were going to be executed. “I really thought that, when the bus stopped, they would kill us,” one protester said. “But one of the PIU officers near me said, ‘Don’t worry, everything will be ok.’ So I realized there were some good people among them.”[50]

The six women arrested on May 9 were held at the PIU headquarters until their release on bail on May 19. The 39 men detained at Janjanbureh prison were held for more than seven weeks without access to legal counsel or family members. “My family would go and ask for me at Janjanbureh, but the staff there would deny I was even there,” one protester said.[51] “That’s why we felt like they were capable of killing us – no one would even know we were there.”

The 39 male protesters were transferred to Banjul’s notorious Mile 2 prison on June 28. Although more than 20 were released on bail on June 29, at the time of writing a dozen remained in detention at Mile 2 in Banjul prison awaiting trial.

One of those detained on May 9, Solo Krummah, died on August 20 in a Banjul hospital, where he had been admitted from Mile 2 prison on August 8. Human Rights Watch learned that Krummah reportedly died of a cranial hemorrhage during a medical operation. Although at least one protester arrested on May 9 told Human Rights Watch that Krummah suffered a wound to his head during his arrest, Krummah also reportedly had a number of underlying health conditions.[52]

A UDP press release on August 21 said that Krummah’s family had repeatedly been denied access to him throughout his custody, and that they had received no information regarding his medical condition during his detention or the care provided to him.[53] Several other protesters detained in April and May have been denied access to adequate medical care for significant periods of their detention.[54] Lamin Dibba, who was injured severely on his eye when a PIU officer hit him on April 16, has yet to receive specialist medical treatment for the injury.[55] Gambian lawyers told Human Rights Watch that a number of the protesters held at Mile 2 remain in need of medical attention, including Dibba.

Violation of the Right to Peaceful Assembly

In total, Gambian security forces arrested more than 90 largely peaceful protesters during April and May. The authorities sought to justify these mass arrests on the grounds that, because the organizers of the demonstrations did not have a permit, the protests were illegal.[56] Gambia’s IEC, when asked about the impact of the arrests on the fairness of the elections, similarly said that the protests had been illegal.[57]

Gambia’s Public Order Act requires those using a public address system at public events to first obtain a permit from the inspector general of police.[58] Under international law on the right to peaceful assembly, as found in article 21 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, while it is reasonable for a government to require demonstrators to notify the authorities in advance of a demonstration, requiring them to get permission is likely to impose an undue obstacle to freedom of assembly.[59]

Solo Sandeng did not have a permit for the April 14 demonstration, which was not organized in the UDP’s name.[60] When asked in April by police whether he had a permit, one protester stated that Sandeng replied that, while he did not have a permit, he had a right to demonstrate.[61]

For the April 16 protest, Ousainou Darboe has explained that, having failed to get information from the Inspector General of Police about Sandeng’s fate, he “did not apply for a permit because it is our constitutional right to hold a peaceful demonstration. And it was peaceful.”[62]

The UN special rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association, as well as the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, have said that organizers of a peaceful assembly, even if unauthorized, should not be subject to criminal penalties.[63]

The UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials set out the basic rules for police during demonstrations. The Basic Principles state that security forces shall “apply non-violent means before resorting to the use of force and firearms,” and that “whenever the lawful use of force and firearms is unavoidable,” law enforcement officials should “exercise restraint in such use and act in proportion to the seriousness of the offence and the legitimate objective to be achieved.”[64]

Prosecution of Protesters and Disproportionate Sentences

At writing, 30 opposition members arrested for taking part in peaceful demonstrations in April and May have been convicted of public order offenses with another 12 awaiting trial.

Eleven protesters arrested with Solo Sandeng on April 14 were convicted on July 21 of public order offenses, including holding a procession without a permit, and also sentenced to three years in prison.

Darboe and 18 others arrested for their role in the April 16 protests, including several other high-ranking UDP members, were convicted of public order offenses on July 20 and sentenced to three years’ imprisonment.[65]

In early June, the nine Gambian lawyers representing Darboe and his fellow detainees refused to participate in the trial to protest that “the accused have been persistently denied their rights,” including the ability to consult with their lawyers outside of earshot of Gambian security officers.[66] Lawyers were generally able to visit the April and May detainees in prison during their trial, although conferences occurred in the presence of security guards, denying them the right to communicate in confidence with counsel and prepare a defense.

Since the July convictions, Gambian lawyers have received only occasional access to the prisoners at Mile 2, with prison officials requiring that they obtain permission from the prison’s director to visit the prisoners. Lawyers are frequently made to wait for hours to receive a response from the prison director, and when permission is granted, given only 5 or 10 minutes with their clients, and always in the presence of prison guards or security officers.[67] One lawyer said that lawyers had had virtually no access to the UDP protesters since the beginning of September. “It’s a clear violation of the right to counsel,” he told Human Rights Watch.[68]

The protesters’ convictions, and the disproportionate three-year sentences protesters received, suggests that the criminal justice system in Gambia, including the judiciary, is beholden to President Jammeh. The UN special rapporteur on torture highlighted the lack of independence of the judiciary in Gambia in a May 2015 report, noting “the lack of judicial activism and independence resulting from Executive interference which undermines the court’s role to ensure accountability.”[69]

In sentencing the April 16 protesters, Justice Eunice O. Dada, a Nigerian national,[70] noted that section 5(5)(a) of the Public Order Act 2009, which prohibits holding a procession without a permit, “prescribes a punishment of 3 years’ imprisonment for every person who partakes of a procession without license.”[71] She indicated that she had no choice but to impose three-year sentences on the accused, because Gambian law “creates no room for the exercise of discretion in the offenses where specific number of years are prescribed and also makes no provision for fine in lieu of custodial sentence."[72]

Gambian defense lawyers told Human Rights Watch that the justification given by Justice Dada for the three-year sentences was flawed. Section 29(2) of the Gambian Criminal Code gives judges the discretion to impose a lesser sentence than that prescribed by law and to impose a fine instead of imprisonment.[73] The law states: “A person liable to imprisonment for life or any other period for an offence against this Code or against any other law may be sentenced for a shorter term” and “a person liable to imprisonment for an offence against this Code or against any other law may be sentenced to pay a fine in addition to or instead of imprisonment.”[74]

Several Gambian defense lawyers said that the sentences imposed on the April 14 and 16 protesters demonstrated executive interference in the judiciary. Bubacarr Drammeh, a Gambian prosecutor who until June worked for the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP), told Human Rights Watch in early July, “It was clear to me when the April 14 and 16 prosecutions began that the executive wanted Darboe convicted as they see him as a challenge to their power.”[75] When he later read the judge’s verdict, he concluded, “The flawed justification for the three-year sentences suggests the outcome was motivated more by politics than by law.”

Harassment of Protesters

Several protesters who avoided arrest, or who were subsequently released on bail, said that they and their family members had been threatened by the police as they left detention, or received subsequent visits to their homes from police or soldiers. Several families, fearful of further abuses, chose to leave Gambia.

Fatoumatta and Muhammed Sandeng, Solo Sandeng’s children, told Human Rights Watch that although they avoided arrest at the scene of the April 16 protest, a police convoy visited their family’s compound later that afternoon. “Some police officers came to our gate looking for us,” Fatoumatta said. “We knew that they had already arrested some of the family members of people involved in the April 14 protest, so we just thought we had to get out.”[76] Sandeng’s wife and nine children never returned to their house and left Gambia a few days later. The husband of Fatoumatta Jawara, who was arrested during the April 14 protest, was reportedly arrested on May 11 after attending a court appearance by his wife.[77] He was released a few days later, although his wife is now serving a three-year sentence.

One protester arrested May 9 recalled that when he received bail on June 29, a senior police officer told him, “You better be careful, as whatever you say, we will know it. People in jail are safe, as they are with us. You are outside, so you are in more danger, as we are watching you.”[78]

He subsequently fled Gambia because he feared he would be rearrested. Another May 9 protester said that, a few weeks after she was released on bail on May 19, soldiers visited her house and threatened her. When they returned the following day, she decided to leave the country.[79]

III. Election Campaign Related Abuses

President’s Threats Against the Opposition

Since the April and May demonstrations, Jammeh has on several occasions threatened opposition groups that they risk retribution if they protest against his government. On May 17, as he began a national tour, he gave a speech in the North Bank region, in which he said: “Let me warn those evil vermin called opposition. If you want to destabilize this country, I will bury you nine feet deep.”[80] During a subsequent June 3 speech as part of the same tour, he said:

Let me tell you something that I can swear by Allah. Any group who says they are against my leadership and that they are against the people’s servant. I swear to Allah that you will not see elections. Police will not catch you, army will not catch you, nobody will catch you, but you will all die one by one before elections.[81]

Opposition activists said that such rhetoric demonstrates that Jammeh, who has survived several coup attempts, conflates legitimate political expression with attempts to overthrow his government. In a June interview, Jammeh said: “[The opposition] they don’t want reforms, they just say, ‘This president must leave.’ They have seen what happened in Tunisia, and they want to do the same thing. But they won’t succeed. I won’t tolerate it.”[82]

On September 6, Gambia’s deputy UN ambassador, Samsudeen Sarr, wrote an open letter to independent presidential candidate Dr. Isatou Touray in a Gambian newspaper, cautioning: “I only would warn you to be mindful of engaging in activities posing a threat to the country’s national security. Because with every political game President Jammeh may tolerate, any activity intended to compromise the national security of the country is nothing he will condone.”[83]

Gambian lawyers said that Jammeh’s inflammatory anti-opposition statements encourage the police and army to use excessive force against protesters. Several protesters described the security forces using language that closely mirrored Jammeh’s own threats against the opposition. Fatoumatta Jawara, who was arrested on April 14 and detained at the NIA, said that before she was beaten, a man told her: “Are you UDP? You people are spoilers, you want to destroy this enjoyable regime but we will deal with you guys.”[84] Another protester arrested on April 14 said that at the NIA he was told, “This is our enjoyable government,

and you want to spoil it.”[85] One protester arrested on May 9 said that a police officer told him, “You’re the ones who want to take our country from us.” Another May 9 protester said that a police officer said, “It’s you people, you want to bring violence. You should have just gone home, instead of going out on the streets like that.”

Jammeh has also sought to use identity politics to undermine support for the April and May demonstrations. During his June 3 speech, Jammeh appeared to portray the protests as a threat to his government by Gambia’s largest ethnic group, the Mandinka, who make up a majority of the UDP’s members.[86] He repeatedly vilified the Mandinka during his speech and said that, “if they think that they can take over the country, I will wipe you out and nothing will come out of it.”

Jammeh’s statement led Adama Dieng, the United Nations Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide, to warn on June 7 that:

I am profoundly alarmed by President Jammeh’s public stigmatization, dehumanization and threats against the Mandinka. Public statements of this nature by a national leader are irresponsible and extremely dangerous. They can contribute to dividing populations, feed suspicion and serve to incite violence against communities, based solely on their identity.[87]

Lack of Neutrality of the Security Services

The arbitrary arrests and abuses in custody committed against opposition members since April reflect President Jammeh’s willingness to use the security forces to consolidate his political power. By doing so, he has undermined the security services’ ability to carry out their role in a neutral and professional manner. “The security forces are his tools, and he uses them to control Gambia by arresting people who don’t share his views,” one presidential candidate told Human Rights Watch.[88]

Former security service members, including senior members of the police and state intelligence services and an army captain and non-commissioned officer, told Human Rights Watch that loyalty to Jammeh was a prerequisite for professional good standing or advancement. Army and police officers publicly display their loyalty to the president as elections approach. One senior NIA officer, who left Gambia following the 2011 elections, said that during the campaign season, “I saw the whole army wearing green t-shirts with Jammeh’s picture on it, saying things like, ‘I am a militant.’ Nothing matters to them other than Jammeh.”[89]

A former senior police officer said that soldiers, even members of Jammeh’s presidential guard, risked dismissal if the leadership thought that they had not voted for Jammeh.[90] “It’s not like before, when the army had standards,” he said. “Now you see them dancing in the street during the campaign, wearing the ruling party’s ‘green green’ colors.”[91]

This is in contravention of the Gambian Constitution which states that a member of the security forces should not “allow his or her political inclinations to interfere with the discharge of his or her official duties” and should not “be a member of, or take part in any association of persons which might prevent him or her from impartially discharging his or her duties.”[92]

Chilling Effect on Political Opposition

The Gambian government’s track record of arresting and intimidating dissenting voices sends a message to opposition politicians and activists that they risk reprisals.

A UDP spokesperson said that the arrest and conviction of Ousainou Darboe would make many people fearful of expressing public support for opposition parties. “It shows ordinary Gambians that no one is safe,” he said. “We already had to work behind closed doors to persuade people to support us but now we have to be even more careful.’[93] Although the UDP on September 1 nominated a presidential candidate and has since held several rallies, the UDP spokesperson said the arrests had deprived the party of the leadership needed to contest the election on an equal footing.[94]

Gambia’s opposition parties do not all experience the level of state restrictions that the UDP, the largest opposition party, has faced in recent years. Several smaller parties said that they had experienced no direct threats by security forces against their party leadership or members. While the UDP has on numerous occasions been refused permits for public events,[95] representatives from several other parties told Human Rights Watch that they were generally able to obtain permits, even if the requirement to do so was a cumbersome administrative obstacle. “It can take almost one month to get a permit,” said one opposition party spokesman. “And so makes it difficult for you to have any continuity in your activities.”[96]

However, even among parties able to operate relatively freely, several opposition members and leaders told Human Rights Watch they strongly believed public opposition to Jammeh’s government put them at risk of arrest. “We are aware that, as we become a strong party, we will be increasingly at risk,” said one opposition spokesman.[97] Party leaders also said that it is the unpredictability—and the arbitrariness—of the government’s abuses that stoke fear among party members and activists. “I know that they might come after me at any time,” said one presidential candidate.[98]

While some presidential candidates have been openly and strongly critical of Jammeh, representatives of several other parties said that they carefully calibrate their activities and speeches to avoid criticism of the government so as to mitigate the risk of government reprisals. “We feel that anything against the regime is likely to attract attention, so we are extremely careful about how we operate,” said one party’s spokesman.[99] “We talk to our supporters to encourage them to not to chant anti-regime messages, and rather to talk about our own messages – our party slogans.” Another party leader said that while the requirement to obtain a permit for a rally creates “an inability to move and operate freely,” they comply with the requirement to avoid arrest. “They will arrest anyone who organizes a protest against the government,” he said. “And we avoid that so that we can compete in the elections.”[100]

Several opposition leaders pointed to the July arrest of Tina Faal, a former parliamentarian and senior member of the opposition Gambian Democratic Congress (GDC), as evidence that the government’s recent crackdown could expand beyond the UDP. Much of the GDC’s leadership, including its leader, Mama Kandeh, and Faal were formerly senior members of Jammeh’s ruling APRC party. Until Faal’s arrest, the GDC had been able to operate relatively freely, and had obtained a permit to conduct a series of rallies outside of Banjul in June 2016.[101]

In public, GDC officials underscore that Faal’s arrest was not connected to her work with the party, and concerns an allegation that she fraudulently sold aircraft parts.[102] However, the timing of Faal’s prosecution – the case dates from 2014 – has led opposition activists to question whether it is an attempt to intimidate the GDC. “Now that the government has seen Tina Faal at GDC rallies,” said one opposition spokesperson, “I think the case has become a threat against the GDC.”[103]

Bubacarr Drammeh, a former Gambian state prosecutor, was actually asked to review the evidence against Faal in May 2015. “Several colleagues in the DPP’s office actually warned me to be careful how I dealt with her case because she was close to President Jammeh,” he told Human Rights Watch.[104] “Given that the case was revived this year, after she became active in the GDC, I think it is politically motivated.”

Repression of the Media

Government actions have severely undermined media coverage of the opposition ahead of the election, both through an inadequate two-week campaign period and the intimidation of the independent press and radio. The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, in its Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression in Africa, affirms that freedom of expression and information “is a fundamental and inalienable human right and an indispensable component of democracy.”[105]

All six opposition parties interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that the combination of journalists’ self-censorship when reporting on politics and the near-complete domination of state media by President Jammeh and the ruling party media denies them a means to effectively communicate to voters. “We lack a platform where we can express our views and manifestos,” one opposition leader said.[106]

There are numerous private newspapers in Gambia, but they have very limited circulation. Gambia’s state media agency, Gambia Radio and Television Services (GRTS), owns the only broadcast TV operation in country, although there are also numerous private radio stations. Gambian politics is discussed on several prominent diaspora online media sites, although limited access to the internet or phone data means they are not accessible to most Gambians. [107]

While there have been fewer arrests and prosecutions of journalists in 2016 than in previous years, the government’s long track record of killing, torturing and arbitrarily detaining independent journalists has created a culture of fear that severely limits journalists’ ability to report freely on either Jammeh’s government or the opposition.[108]

In 2013, two years after the last presidential election, the government enacted a series of repressive laws that further curtailed freedom of expression and the media.[109] One law increases penalties for “providing false information,” while another criminalizes anyone using the internet to spread “false news” about the government or civil servants.[110] The government has invoked these laws to prosecute people it deems responsible for critical speech.[111]

“There’s very few outspoken editors and journalists left,” journalist Sainey M.K. Marenah told Human Rights Watch, after he described how he was arrested in January 2014 for “spreading false news” after publishing an article on the defection of youth supporters from the ruling party to the opposition. “Media is even more conscripted than when I was arrested.”[112]

Journalists are aware that they face particular risks as elections approach. “There’s a lot of self-censorship from reporters during the elections,” said Sanna Camara, a Gambian journalist, now in exile, who was arrested and charged with false publication in April 2014 for publishing an article on human trafficking in Gambia. “Journalists are scared to report to give too much press to the opposition.”[113] In advance of the election, the government has periodically blocked several social media sites used by Gambians to communicate with journalists from diaspora news sites, including WhatsApp and Viber.[114]

Despite the risks, a handful of Gambia’s newspapers do give some coverage to opposition parties. However, opposition activists say that newspapers are not an effective medium for reaching many voters, particularly in rural areas. “Given our country’s 50 percent literacy rate, newspapers just aren’t very read outside the capital,” an opposition spokesman told me. “It’s radio and television that is needed to reach people in rural areas.”[115]

Gambia’s private radio stations typically avoid political news or discussion. One exception, Teranga FM, which previously discussed topical news stories in local languages, ceased doing so after the detention in July 2015 of its managing director, Alhagie Ceesay.[116] “They’ve closed the radios that used to cover us, and now everyone is very careful,” said one opposition leader.[117] “The government has a stranglehold on information channels.”

In the absence of a free and independent media, many Gambians rely on state radio and television for information on current affairs. The IEC told Human Rights Watch that during the two-week campaign period that precedes election day, each opposition party will have the right to equal airtime on state television and radio, with the number of minutes allocated dependent on the number of candidates who contest the election.[118] A Commonwealth report concluded that requirement for equal airtime during the campaign period was respected during the 2011 elections.[119]

However, prior to the official campaign, state media is dominated by the president and the government. “Ninety percent of programs promote the government,” said one Gambian journalist, now in exile.[120] “If you watch Gambian television, you’d think everything is okay in the country,” said another.[121]

Gambia’s constitution states that all “state owned newspapers, journals, radio and television shall afford fair opportunities and facilities in the presentation of divergent views and dissenting opinion.”[122] In reality, however, opposition parties have no access to state media to publicize their activities and build their brand. “State television, funded by tax payers, should provide divergent views of the people of Gambia,” said an opposition leader. “But no opposition party leader is allowed to use state media. We ask regularly for coverage, but neither state radio or TV will give us air time.”[123]

The access opposition parties are given during the two-week campaign period does not compensate for the government’s near-monopoly of state radio and television in the lead-up to the campaign. In its report on the 2011 presidential elections, a Commonwealth Expert Team stated that although all parties had equal time for election broadcasts during the official two-week campaign period, the media coverage generated by Jammeh in the months before the campaign meant that “the political advantage in the 2011 presidential campaign clearly lay with the incumbent.”[124] Six opposition parties, including the UDP, in June 2015 requested increased access to state media and a three-month campaign period “to enable the voters to be well informed and create a level ground before elections.”[125] Despite this request, opposition parties still have no access to state media before the two-week campaign period.

Several diplomats told Human Rights Watch that the IEC had been more open to dialogue about the electoral framework than in previous election cycles. However, when asked in September by an opposition spokesperson about increased access to state media, the IEC responded that while it could guarantee equal access during the two-week campaign, it had no power to regulate opposition access to media before the campaign begins.[126] The IEC told Human Rights Watch that decisions on access to the media before the campaign are made by the government and the state broadcaster.[127]

Use of State Resources for Campaigning

While the opposition faces considerable difficulty in reaching voters, President Jammeh uses the apparatus of the state to promote his own candidacy. “The ruling party sees no difference between state and party resources,” said one opposition leader.[128] “It uses government vehicles and mobilizes the army, police, and civil service as a means of its campaign.”

In its report on the 2011 presidential election, a Commonwealth Expert Team said that “the use by the APRC of government resources and personnel to support President Jammeh’s campaign was nationwide and overt,” noting that this was a violation of Gambia’s election laws.[129] The report cited several examples of the blurring of state and party lines, including use of the offices of regional governors as organizational centers for the APRC campaign and the use military vehicles to transport APRC supporters.[130]

Opposition activists complain, in particular, that Jammeh uses his annual, constitutionally mandated “Meet the People” tours to promote his candidacy. The Commonwealth report concluded that a “Meet the People” tour in July 2011 “amounted to campaigning and gave [Jammeh] an undue advantage in the lead-up to the presidential election.”[131]

A former NIA official who accompanied Jammeh on the July 2011 tour told Human Rights Watch:

These tours are like their own political convention. Jammeh has different ways to control people. He gives money to the elders and to youth leaders. He makes promises that he is going to change lives, all the things that a poor person would want to hear. He visits the projects that he has implemented and positions them as things that will cater for the welfare of his people. When he is visiting opposition areas, he will often say, if you don’t vote for me there will be no development here in the next fifty-five years. He wants to portray that, whether Gambians vote for him or not, he will always win.[132]

As Jammeh embarked on this year’s “Meet the People” tour in May, the Daily Observer, a pro-government newspaper, reported on May 18 that he told a crowd in the North Bank Region that he is not conducting the nationwide tour to campaign for reelection.[133] However, Jammeh has used speeches while on his tour to criticize and threaten the opposition.[134] “It’s not just a president visiting development projects,” one opposition politician told Human Rights Watch.[135] “It was on this last ‘Meet the People tour’ when he threated the opposition. What more could show that this is a political speech?”

The official images archived by the Gambian government on the conclusion of the first leg of the 2016 “Meet the People” tour in Banjul on May 28 show Jammeh riding on the roof of an armored military vehicle through roads thronged with crowds, with some supporters holding signs that read “Yaya for life” and “100% APRC.”[136] Many of the images also appear to show Gambian soldiers, in uniform, showing their support for Jammeh by waving tree branches.

IV. International Response

The deaths in custody, arbitrary arrests and disproportionate sentences that followed the April 14 and 16 protests have led to public statements by ECOWAS,[137] the African Union,[138] the UN secretary-general,[139] the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights,[140] the United States,[141] the European Union[142] and the United Kingdom.[143]

Gambian human rights activists underscored the particular importance of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, whose headquarters are in Banjul, publicly denouncing abuses in advance of the December elections. During its April 2016 session, the African Commission stated that it was “deeply concerned by the reports of events that took place on 14 and 16 April 2016” and called on the government to investigate reports of deaths in custody and alleged beatings of demonstrators and ensure the speedy release of all persons arrested.[144]

Gambian human rights activists and opposition party officials told Human Rights Watch that statements by regional and international actors were important as they demonstrate to President Jammeh’s government that its actions are under scrutiny. Indeed, several activists said that they believed the international criticism that followed the death of Solo Sandeng led the government to at least acknowledge that he had died in custody.[145] He subsequently fled Gambia because he feared he would be rearrested. Another May 9 protester said that, a few weeks after she was released on bail on May 19, soldiers visited her house and threatened her. When they returned the following day, she decided to leave the country.[146]As evidence of the impact of engagement with the government, diplomats also point to the organization by the Ministry of Justice of August and September workshops giving civil society the opportunity to provide input on a draft law creating a Gambian human rights commission.

While important, however, engagement with and international scrutiny of the Gambian government has in reality not led the government to significantly improve its conduct. When questioned about Sandeng’s death in a May interview, President Jammeh responded by saying that human rights groups and UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon could “go to hell.”[146] The government has so far not released Fanta Jawara, a dual Gambian-US citizen arrested during the April 16 protests, despite calls for it to do so by Samantha Power, the US ambassador to the United Nations, and four US congressmen.[147]

Several interlocutors expressed concern at the extent to which decision-making on key political and human rights issues is concentrated in the hands of the executive branch, while also expressing frustration with regards to how best to influence the president. Former Gambian government officials told Human Rights Watch that Jammeh’s personal sign-off is sometimes required for even relatively minor decisions. And Jammeh himself only very rarely meets with senior diplomats, meaning that while it can be easy for international interlocutors to meet ministers and civil servants, they often lack the authority to act.

The US and EU have in the past sought to demonstrate to the Gambian government that its failure to improve respect for human rights has consequences. The EU in December 2014 withdrew €13 million of development assistance to Gambia over concerns about its human rights record.[148] EU development assistance has since restarted, but is channeled through non-state actors. The US in 2014 dropped Gambia from its preferential trade agreement, the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act.[149] In May 2015, US National Security Advisor Susan Rice said she was “deeply concerned about credible reports of torture, suspicious disappearances and arbitrary detention at the government’s hands,” and added that the US government is “reviewing what additional actions are appropriate to respond to this worsening situation.”[150]

Given the government’s persistent unwillingness to accept international calls to improve its human rights record, ECOWAS, the EU and the US should now consider imposing sanctions on the Gambian government. They should set a series of benchmarks for the government to meet prior to and immediately after the December election, and should impose sanctions if those benchmarks are not met. Relevant benchmarks should include the immediate release of all peaceful protesters; initiating an open and rigorous investigation into opposition deaths in custody; respecting opposition parties’ rights to hold peaceful protests, meetings, and rallies; granting opposition parties access to state media outside of the official campaign period; ending the use of state resources for campaigning; and demonstrating respect for the press.

ECOWAS and the AU have deployed a pre-electoral technical mission to evaluate the election environment ahead of the December election.[151] If the aforementioned benchmarks are not met, ECOWAS should, in particular, consider invoking the sanctions available to it under its Protocol on Democracy on Good Governance, which elevates the principle that, “every accession to power must be made through free, fair and transparent elections” to a constitutional principle shared by all ECOWAS member states.[152] Under the Protocol, where there is a “massive violation of human rights” in a member country, ECOWAS can impose sanctions on the state concerned. These sanctions may include refusal to support the candidates presented by the state for elective posts in international organizations; refusal to organize ECOWAS meetings in the member state concerned; and suspension of the member state from all ECOWAS decision-making bodies.[153]

The US and the EU should impose targeted sanctions, such as visa bans and asset freezes, on the Gambian ministers and officials who oversee or lead institutions responsible for the worst abuses, including the Jungulers and the NIA.[154] By focusing on individuals, targeted sanctions impact the personal interests of the government’s security apparatus but do not deny ordinary Gambians development assistance.

On concluding a September visit to Banjul, David Martin, a member of the European Parliament, said that if the human rights situation does not improve, “the European Parliament has indicated that there would be a need to consider targeted sanctions on officials responsible for serious human rights abuses.”

On October 1, 2016, the US imposed a ban on new visas for Gambian government officials and their families in response to the Gambian government’s failure to accept Gambians to be deported from the US.[155] That the government is reportedly preparing to now accept deportees may indicate that targeted sanctions, if linked to human rights benchmarks, could help move the government toward change.

Recommendations

To President Yahya Jammeh and the Government of Gambia

- Release immediately and drop any charges against all those detained for exercising their rights to peaceful assembly or to freedom of expression or association.

- Quash the convictions and order the release of all those convicted for engaging in peaceful protests.

- Allow visits to all places of detention by: representatives of independent human rights and humanitarian organizations, lawyers and medical professionals.

- Ensure access to appropriate medical treatment for prisoners.

- Establish a credible, independent and impartial inquiry into the treatment in custody of protesters arrested in the April and May 2016 demonstrations, including the deaths of Solo Sandeng and Solo Krummah. Appropriately prosecute all officials, regardless of title or rank, implicated in wrongdoing.

- Publicly affirm the rights of all political parties, the media, and civil society organizations, including the rights to freedom of expression, association, and peaceful assembly.

- Issue a clear and public statement to all government officials and state security forces that any acts violating the rights of members of opposition parties, journalists, and members of civil society organizations will be promptly investigated and those responsible appropriately disciplined or prosecuted.

- Publicly instruct Gambia Radio and Television Services to allow full, open reporting and commentary on all issues of public interest, including political, accountability and transparence matters.

- Publicly instruct Gambia Radio and Television Services to ensure the voices of opposition parties are heard before the official election campaign begins and are provided equal access during the campaign.

- Ensure that state resources are not used for the purpose of political campaigning, including by:

- Prohibiting political parties from using state buildings or vehicles for campaigning;

- Ensuring state funds are not used for the purposes of campaigning by the president and the ruling party, and;

- Prohibiting civil servants and security forces from participating in political rallies while on duty and in uniform.

To the Gambian Police

- Allow peaceful public events and rallies, including by opposition parties, even if the organizers have not complied with the Public Order Act requirements on police notification or permission.

- Process requests to obtain a permit for public assemblies or for use of a public address system in a timely manner.

- During public gatherings, abide by the UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials.

- Ensure that persons taken into custody are treated with full respect for their basic rights, promptly brought before a judge, and held only in official places of detention; and ensure that all detainees are provided with immediate and regular access to family members and legal counsel.

To the National Assembly

- Repeal or amend all legislation infringing upon the rights to freedom of expression, association, and peaceful assembly, including:

- The Public Order Act requirement of permits for public assemblies, which should be amended to require only notification to the authorities of planned public assemblies;

- The Criminal Code offenses of sedition (section 52), criminal libel (section 178), spreading false information (section 181);

- Provisions of the Information and Communication Act of 2013 that include censorship of online expression (section 173A).

To the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the African Union, the United States, and the European Union

- Consistently publicly condemn serious human rights violations in Gambia, and raise concerns with government officials at all levels.

- Ensure any election monitors deployed for the 2016 elections have a mandate to document and publicly report on human rights violations.

- In the absence of substantial human rights improvements in Gambia, consider imposing sanctions, specifically:

- Suspending Gambia from all ECOWAS decision-making bodies under article 45 (2) of the ECOWAS Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance;

- Imposing travel bans, asset freezes and other targeted sanctions on officials responsible for serious human rights abuses.

To the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR)

- Consistently publicly condemn serious human rights violations in Gambia, and raise concerns with government officials at all levels.

- Make clear to the government that should it fail to comply with Commission resolution and requests, including those relating to opposition freedoms, the Commission will consider referring Gambia to the African Union Executive Council for non-compliance.

To UN Human Rights Council Member Countries

- In the absence of substantial human rights improvements in Gambia, adopt a resolution to establish regular monitoring, reporting, and interactive dialogue on the human rights situation.

To relevant UN Special Rapporteurs, including on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions and Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and of Association

- Consider requesting visits to Gambia to examine human rights violations committed against political opposition, journalists and other dissenting voices.

Acknowledgments

This report was researched and written by Jim Wormington, researcher for the Africa Division at Human Rights Watch.

The report was edited by Corinne Dufka, Associate Director for the Africa Division. James Ross, Legal and Policy Director, and Babatunde Olugboji, Deputy Program Director, provided legal and programmatic review respectively.

Human Rights Watch is especially grateful to the Gambian victims who courageously agreed to be interviewed for this report. Human Rights Watch also recognizes the assistance provided by partner organizations, including Amnesty International, Article 19, and the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Production assistance was provided by Lauren Seibert, West Africa Associate; and Jose Martinez, Acting Administrative Manager.

Annex: Letter to Gambian Government

October 19, 2016

Sulayman Samba

Secretary General, Office of The President

State House

Republic of The Gambia

Banjul, Gambia

Dear Mr. Samba,

We are writing to request the response of the Gambian government in regard to research conducted by Human Rights Watch on the human rights dimensions of your country’s upcoming December presidential elections. We plan to release a report detailing our findings in early November.

The results of our research are summarized below. We would appreciate the opportunity to integrate into our report the Gambian government’s responses to our findings. We have, in this regard, attached a list of relevant questions for your government. To allow us to reflect your government’s response in our report, we would be very grateful for a response to our findings, and the questions below, by October 30, 2016.

Between March and October 2016, Human Rights Watch conducted detailed interviews with dozens of members of Gambian political parties, journalists, civil society leaders, lawyers, retired Gambian civil servants, and international organizations and representatives.

The principal conclusion of our research is that the arbitrary arrests, convictions and mistreatment of peaceful protesters by state officials since April, coupled with the government’s longstanding domination of state media and use of state resources for campaigning, have severely diminished prospects for a free and fair election in December.

In order to ensure better respect for civil and political rights, and to meet Gambia’s obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, Human Rights Watch recommends that the government take the following steps.

Recommendations to the Government of Gambia

- Release all peaceful protesters;

- Conduct transparent and impartial investigations into deaths in custody of members of the political opposition;

- Ensure that state security forces respect all political parties’ rights to freely and peacefully campaign without fear of harassment or arrest;

- Ensure opposition parties have access to state media outside the framework of the official campaign;

- Take all necessary steps to ensure that the government officials and security forces do not harass or intimidate journalists and human rights defenders in advance of the election;

- Cease the use state resources for campaign purposes.

Human Rights Watch calls upon Gambia’s key international interlocutors, including the Economic Community of West African States, the European Union and the United States, to consider additional measures if Gambia’s human rights situation does not improve ahead of the December elections.

Our research findings are summarized below.

Sumary of Conclusions

Response to Peaceful Protests

- The arrest of largely peaceful protesters on April 14 and 16 and May 9 violated the right to peaceful assembly, even if the protesters did not have a permit. Under international law, as found in article 21 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, while it is reasonable for a government to require demonstrators to notify the authorities in advance of a demonstration, requiring them to get permission is likely to impose an undue obstacle to freedom of assembly.[156]

- The force used by security forces to disperse protesters at the April 14 and 16 and May 9 protests, including the beating of protesters with batons, was disproportionate. While several witnesses stated that some protesters threw stones at members of the Police Intervention Unit (PIU) who sought to disperse the protesters, they did so only after the PIU officers began beating protesters with batons.

- The conviction and sentencing of 30 peaceful protesters to three-year prison terms, including UDP leader Ousainou Darboe, also violated the right to peaceful assembly. The UN special rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association and the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights have both said that organizers of a peaceful assembly, even if unauthorized, should not be subject to criminal penalties.[157]

- The Gambian government severely mistreated many protesters once they were in state custody. Solo Sandeng, the UDP National Organizing Secretary, reportedly died on April 15 as a result of injuries sustained from beatings at the National Intelligence Agency (NIA), and at least seven other protesters were hospitalized after being severely beaten while at the NIA.

- A number of protesters held at Mile 2 prison and in other detention facilities have reported that they have received inadequate medical attention. One protester arrested on May 9, Solo Krummah, died on August 20 at a Banjul hospital. Krummah’s family have stated that they were repeatedly denied access to him throughout his custody, and were given no information regarding his medical condition during his detention, the care provided to him, or the cause of his death.

Election Campaign-Related Issues

- The arbitrary arrests, mistreatment and prosecutions of peaceful protesters carried out by the government since April, coupled with public statements that appear intended to threaten opposition groups, have reinforced a climate of fear among many opposition politicians and activists that severely limits their ability to criticize the government, as is protected under international law.

- The two-week campaign period, coupled with the government’s near-monopoly of state media at other times, makes it extremely difficult for opposition parties to engage meaningfully with potential voters. Although Gambia has numerous private newspapers and radio stations, many critical journalists temper their reporting of the government out of fear of reprisal.

- The President and the ruling Alliance for Patriotic Re-Orientation and Construction (APRC) routinely use state resources for campaigning, including government vehicles and buildings, and mobilize civil servants and security force members to act on behalf of his reelection. Before campaigning even begins, the President has exploited his nationwide and constitutionally mandated “Meet the People” tour to promote his candidacy.

- The government’s intimidation of opposition leaders and the media, as well as its use of state resources for campaigning, present a clear threat to the fairness of the 2016 presidential elections, as well as legislative and local government elections scheduled for April 2017 and April 2018 respectively.

Questions

- What actions, including the issuance of public statements, will your government be taking to ensure that political opponents, journalists and supporters of all political parties will be able to enjoy their rights to freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly before, prior to, during and after the December 2016 elections?

- What is the status of investigations into the deaths in custody of Solo Sandeng and Solo Krummah?

- What actions have you taken, or will you take, to investigate and prosecute members of the Gambian security forces responsible for the mistreatment and deaths in custody of detained protesters?

- What actions will you be taking to ensure that opposition parties have meaningful access to state media prior to, and during, the two-week election campaign?

- What actions will you take to ensure that the ruling party does not use state resources for campaigning during the 2016 presidential elections?

We thank you very much for the continuing dialogue between your government and Human Rights Watch regarding Gambia’s human rights situation. To allow us to integrate your reply into our report, we would welcome your response to the findings and questions raised in this letter by October 30, 2016. Any response may be sent to xxxxxxxxxxx or xxxxxxxxxxx.

Sincerely,

Corinne Dufka

Associate Director, Africa Division

Human Rights Watch

CC:

Sheriff Bojang, Minister for Information

Sheikh Omar Faye, Ambassador of The Gambia to the United States