(Washington, DC) – Authorities in Paraguay destroyed crucial evidence in the killing of two 11-year-old Argentinian girls by state forces and violated their own investigative protocols and international human rights standards, Human Rights Watch said today. The Paraguayan government should ensure an independent, prompt, impartial, and transparent investigation into the killings.

On September 2, 2020, members of the Joint Task Force, a military-led elite unit that includes police and counter-narcotics agents, allegedly killed Lilian Mariana Villalba and María Carmen Villalba during an operation against a camp of the Ejército del Pueblo Paraguayo (Paraguayan People’s Army or EPP), an armed group, in a forested area about 360 kilometers northeast of Asunción. The mother of one of the girls, who were cousins, told Human Rights Watch that the girls were born and lived in Argentina but were in the camp visiting their fathers, who are members of the armed group.

“All signs indicate that the investigation into the killings has been woefully inadequate,” said José Miguel Vivanco, Americas director at Human Rights Watch. “The Paraguayan government should immediately allow Argentinian forensic experts to conduct an autopsy and grant them and the victims’ families full access to the evidence. The longer the government delays exhumation, the more likely that any evidence from the remains will be lost.”

Shortly after the raid, Paraguayan President Mario Abdo Benítez traveled to the camp, called the operation “successful in every sense,” and said that two female members of EPP had been killed. Nobody else was killed. One Task Force agent was slightly injured.

Human Rights Watch reviewed the authorities’ public statements about the case and publicly available evidence. In response to a Human Rights Watch request, the Independent Forensic Expert Group (IFEG) of the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims (IRCT), an international group of pre-eminent forensic experts, provided its expert opinion on some elements of the investigation.

Human Rights Watch found that irregularities have marred the investigation into the killings from the very beginning, including that the authorities:

- Hastily buried the victims without an autopsy

- Burned the victims’ clothing

- Maintain, based on an unreliable forensic test, that one of the 11-year-old victims had fired a gun

- Made a shooting range determination that cannot be substantiated based on forensic evidence

- Barred a representative of the families from a forensic examination of the remains and denied them access to the investigation

Onder Ozkalipci and Karen Kelly, two forensic medical experts affiliated with IFEG who have extensive international experience, concluded that the destruction of the girls’ clothing “represents the destruction of crucial evidence that violates the most basic and fundamental criminal investigative and forensic principles.”

International standards that mandate an effective investigation in all cases of killings by state forces require preserving such evidence. The director of forensic science at Paraguay’s Prosecutor’s Office, Pablo Lemir, said in a September 7 radio interview that clothing is “key for criminal investigations” and must be preserved under the country’s own protocol.

Cristian Ferreira, the Paraguayan forensic expert who first examined the bodies, told the media that the girls were shot from the front and then from the back and the side, leaving the bodies face down on the ground. “The position of the bodies shows both [girls] were obviously fleeing” the state forces attacking the camp, the expert said. The authorities have not released any images of the bodies as they were found.

Ferreira said that, based on his external examination of the injuries, the victims had been shot from a distance of between 10 and 20 meters. In contrast, the two IFEG experts said that forensic analysis cannot determine shooting distances exceeding approximately 1.5 meters, since “bullets fired from 1.5, 50 or 150 meters will produce gunshot entrance wounds with identical appearances.”

Police conducted a paraffin test to identify gunshot residue on the victims’ hands and thus determine whether they had fired a gun. A prosecutor said it was positive for one of the girls and negative for the other. But the IFEG experts asserted paraffin tests are unreliable and that their value is “marginal, at best,” as a variety of substances can trigger a positive result – beans, lentils, and other leguminous plants, urine, fertilizer, tobacco, fingernail polish, soap, and even tap water.

The Paraguayan government spent days insisting that the victims were much older than they really were, despite evidence provided by their families and corroborated by the Argentinian government. Because of the controversy surrounding their age, Paraguayan officials exhumed the bodies and, after DNA and bone analysis, Lemir confirmed the girls were 11 years old.

After that examination of the remains, Lemir said that one girl was shot seven times – from the front, the back, and the side – while the other girl was shot twice, from the front and the side. A lawyer representing the victims’ families told Human Rights Watch that the authorities did not allow her to be present during a forensic examination on September 5 and have continued to deny her access to the investigation, in violation of international human rights standards.

On September 15, the Argentinian government asked Paraguay to authorize the Argentinian Team of Forensic Anthropology (EAAF, in Spanish), a well-respected group of professionals with experience in forensic investigations around the world, to exhume the bodies and conduct an autopsy. They have not received authorization. The two IFEG experts recommended exhuming the bodies “in haste” to preserve any remaining evidence, given the deterioration of remains over time.

On September 9, the Paraguayan Human Rights Coordinating Group (Coordinadora de Derechos Humanos del Paraguay, Codehupy), a coalition of human rights organizations, sent a letter to Paraguay’s Congress requesting the creation a commission to investigate the case. Congress has not responded yet, according to the coalition. Human Rights Watch supports its petition.

EPP is an armed group allegedly responsible for homicides and several kidnappings, including the September 9 kidnapping of former vice president Óscar Denis, who remains missing.

Paraguay’s international human rights obligations require it to conduct thorough, prompt, and impartial investigations into killings by state agents. The international standard for conducting autopsies and other forensic analysis is the United Nations Manual on the Effective Prevention of Extra-legal, Arbitrary, and Summary Executions, known as the Minnesota Protocol. Paraguayan authorities have not complied with the basic investigative steps laid out by that protocol, Human Rights Watch said.

“Paraguay’s authorities attribute very serious crimes to members of the EPP, who, if proven guilty after an independent investigation and trial, should be held accountable,” Vivanco said. “But state action also needs to be within the bounds of the law. Any killing by state forces should be thoroughly investigated.”

For details about the killings and subsequent events, please see below.

Details of the Raid

At around 10 a.m. on September 2, 2020, the Joint Task Force, a military-led elite unit that includes police and counter-narcotics agents, conducted an operation against a camp of the Ejército del Pueblo Paraguayo (Paraguayan People’s Army or EPP), an armed group, in a forested area in Yby Yaú, a municipality about 360 kilometers northeast of Asunción, Paraguay’s capital.

The raid was the result of “seven or eight months of intelligence work,” Gen. Héctor Grau, the Joint Task Force commander, said later. A Task Force spokesperson also said the force had an agent who infiltrated the area and that the operation “was the product of intelligence work from some time, and not a casual encounter.” Officials did not say whether, given that intensive intelligence work, they knew there were children in the camp.

Shortly after the raid, Paraguayan President Mario Abdo Benítez said that two female members of EPP had been killed. The authorities have not said how many other people were at the camp. Anyone else there fled after the raid, Grau said. The authorities also have not disclosed how many state agents participated nor which weapons they used.

Destruction of Crucial Evidence

After the shooting, the authorities moved the bodies to a public health clinic. Paraguayan media published two pictures of the victims taken there, which show their faces and part of their bodies. The girls are shown wearing military fatigues that look new and clean, and have no apparent bullet holes or bloodstains. In contrast, the girls’ faces and hands are dirty and have blood stains.

At a news conference on September 3, General Grau claimed that “relevant authorities and the forensic expert” decided to bury the bodies the same day, following a protocol to limit the spread of Covid-19. A prosecutor said they burned the victims’ clothing for the same alleged reason. The government did not claim the girls had Covid-19, or even that there were any suspicions that they were infected.

Contrary to the authorities’ statements, the Health Ministry’s Covid-19 protocol does not apply to this case, as it expressly says that the Prosecutor’s Office’s forensic medicine protocol should be used in cases of violent death. And even if authorities erroneously applied the Health Ministry’s protocol, that protocol does not order immediate burial and destruction of clothing.

The authorities did not burn other clothing, blankets, food packages, and other objects found at the camp, which they displayed for the media on September 3. They did not explain why they handled the girls’ clothing differently.

The Prosecutor’s Office’s forensic science director, Pablo Lemir, said in a September 7 radio interview that the protocol applicable to this case and to any violent death during the pandemic requires preserving clothing and any other evidence and waiting for “a prudential time period” before examining them. Lemir said clothing is “key for criminal investigations.”

Cristian Ferreira, the forensic expert who visited the site the day of the shooting, said that, after looking at the victims’ injuries, he estimated they were shot from a distance of between 10 and 20 meters.

In their report to Human Rights Watch, the IFEG experts said that shooting distance cannot be assessed for distances exceeding approximately 1.5 meters, since “bullets fired from 1.5, 50 or 150 meters will produce gunshot entrance wounds with identical appearances.” Shots fired at closer range may leave soot, fire, and smoke marks on clothing, but “without the clothing, the distance from the gun to the victim cannot be correctly determined,” the experts said.

Ferreira said on September 3 that he did not conduct an autopsy before the victims were buried because it was “unnecessary.” Lemir contradicted him later, saying the protocol mandates refrigerating remains for 24 hours and conducting an autopsy afterward.

Authorities Falsely Insisted the Girls Were Older

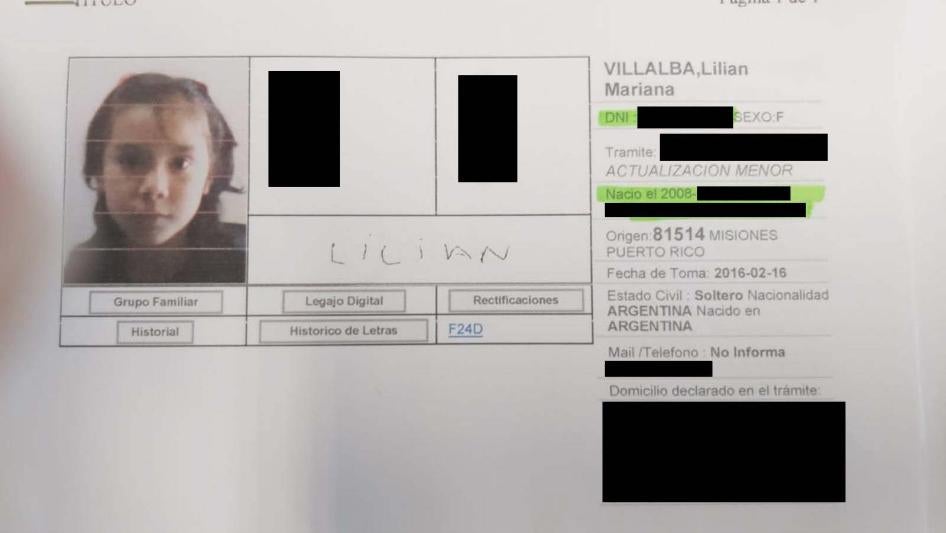

At the September 3 news conference, Ferreira said that one of the victims was 15 and the other was “17 or 18.” The next day, relatives provided local media with the victims’ Argentinean identification papers, showing that they were cousins Lilian Mariana Villalba and María Carmen Villalba, both aged 11. The Argentinian government confirmed that information and called on Paraguay to investigate the case and identify those responsible for the killings.

General Grau responded that the families had provided false data to obtain those identification cards, but he did not produce any evidence to back that allegation. The Paraguayan government insisted the girls were not 11.

Because of the controversy surrounding their age, Paraguayan officials exhumed the bodies and transported them to Asunción, where Lemir conducted a forensic examination on September 5. According to Lemir, the objective of the examination was to determine the girls’ age; however, he also took tissue samples, examined their wounds, and collected bullet fragments. DNA and bone analysis confirmed that the girls were in fact 11, he said.

Unreliable Gunshot Residue Test

Ferreira said he found the two girls’ bodies face down at the site and that he believed they were shot as they fled. He also said one girl was holding a handgun and the other one was holding a gun and a rifle. The authorities have not released photos of the bodies as they were found.

Ferreira said that officials moved the bodies to the Yby Yaú public health clinic and conducted a search there, finding “almost 200 munitions” in the pockets of each girl.

A prosecutor said a paraffin test revealed that one of the girls had opened fire with a gun, while the other had not. But paraffin tests are unreliable, according to the IFEG experts, as substances other than gunshot residue can cause a positive result. The experts point out that courts in the United States and Europe have rejected this test as evidence since 1959.

The prosecutor said one girl had fired a 9-millimeter gun. However, the authorities have not publicly presented or released any ballistic analysis of that gun, nor of any other weapons found at the camp that would indicate whether the alleged EPP members had fired them. The authorities also have not said whether they seized the weapons used by state agents or carried out ballistic analysis of those weapons. That analysis could help determine the circumstances of the incident, such as who opened fire and which weapons held the bullets that killed the girls.

Lack of Transparency

Although the authorities have opened an investigation, they have released very little – and highly selective – information about the investigation and the steps taken so far. They said there are no video recordings of the raid. They also have not made public whether prosecutors have interviewed participants in the raid or conducted any ballistic analysis on their weapons.

A lawyer representing the victims’ families told Human Rights Watch that authorities did not allow her or the Argentinean consul in Paraguay to be present during the September 5 examination of the bodies.

The lawyer also requested access to documentation about the case. In a response dated September 25, a prosecutor denied her access, saying that Paraguayan authorities first needed to confirm whether the victims were indeed the daughter and niece of Myriam Viviana Villalba, whom the lawyer represents. In a September 28 response to another request, a different prosecutor similarly denied her access, saying that Paraguayan authorities first needed to determine whether the lawyer’s power of attorney, signed in Argentina, was legal in Paraguay, and whether the authentication by the Argentinian consul in Paraguay was valid. Three months after the killings, the families still do not have access to the case files.

The Paraguayan government accused the EPP of using the two girls as child soldiers and as “human shields.” Family members said their fathers were members of the armed group, but they denied that the girls themselves were members. They said that the children had lived in Argentina all their lives and had traveled to Paraguay in November 2019 to meet their fathers for the first time. The girls were unable to return to Argentina after Paraguay imposed strict restrictions on movement to contain the spread of Covid-19, Myriam Villalba, the mother of one of them and aunt of the other, told Human Rights Watch.

Paraguay’s Duty to Investigate and Provide Information

The right to life, as protected under international law – including in both the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the American Convention on Human Rights, to which Paraguay is a party – obliges states to refrain from the arbitrary deprivation of life and to effectively investigate all killings implicating the state. The Inter-American Court of Human Rights has ruled that states should put in place “an effective legal system to investigate, punish, and redress deprivation of life by [s]tate officials or private individuals.”

The Minnesota Protocol on the Investigation of Potentially Unlawful Death, which provides standards for the investigation of deaths caused by state agents, says the duty to investigate is “an essential part of upholding the right to life.” Investigations and prosecutions “are essential to deter future violations and to promote accountability, justice, the rights to remedy and to the truth, and the rule of law,” the protocol says.

The protocol was originally drafted to supplement the UN Principles on the Effective Prevention and Investigation of Extralegal, Arbitrary and Summary Executions, which set out international legal standards to prevent and investigate potentially unlawful killings. Those principles establish that investigations into those cases must be “thorough, prompt and impartial,” and capable of leading to a determination of whether the force used was justified under the circumstances and to the identification and punishment of those responsible.

The Inter-American Court of Human Rights has ruled that officials have the obligation to provide the family of victims with “full access and the capacity to act, at all stages and levels of said investigations.” Similarly, the UN Principles on the Effective Prevention and Investigation of Extralegal, Arbitrary and Summary Executions states that families of the victims and their legal representatives shall have access to “all information relevant to the investigation.”

The Minnesota Protocol also establishes that investigations into killings by state agents need to be transparent and that, in addition to access to the investigation for victims’ families, there needs to be a level of public scrutiny. It states that “any limitations on transparency must be strictly necessary for a legitimate purpose, such as protecting the privacy and safety of affected individuals, ensuring the integrity of ongoing investigations, or securing sensitive information.” The protocol makes clear that states may under no circumstances restrict transparency in a way that would result in impunity for those responsible for abuses.

International Standards for Forensic Investigations

The UN Principles on the Effective Prevention and Investigation of Extralegal, Arbitrary and Summary Executions establish that investigations need to include “an adequate autopsy, collection and analysis of all physical and documentary evidence and statements from witnesses.”

The international standard for conducting autopsies and other forensic analysis is the Minnesota Protocol, which provides detailed guidelines on adequate photographs, X-rays, descriptions of external wounds and their trajectory, dissection of tissue, sampling of clothing and skin, and detection of firearm discharge residue on the hands of victims, among other necessary steps.

Since the authorities have not granted access to the forensic reports to the families of victims nor released them to the public, it is not known how comprehensive the forensic examinations were. However, their public statements have revealed that they did not comply with basic investigative steps contained in the Minnesota Protocol, Human Rights Watch said.

For instance, the protocol establishes that the body of the victim should be placed in a body bag following chain-of-custody procedures and kept in refrigerated or cool storage to inhibit further decomposition.

The protocol also instructs investigators to preserve any trace evidence, such as gunshot residue, by placing the hands of victims in paper bags and then sealing them with tape, and to photograph and preserve any gunshot residue for analysis. The protocol also calls for the secure preservation of all evidentiary material, including clothing.

In addition, the Minnesota Protocol establishes that family members should be entitled to have a representative present during the autopsy.

Paraguayan authorities did not follow any of those steps.

The Authors of the IFEG Report

The IFEG is an international body of 42 pre-eminent independent forensic specialists from 23 countries who are recognized global leaders in the medico-legal investigation of torture, ill-treatment, and unlawful killing. The IFEG is coordinated by the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims (IRCT).

Onder Ozkalipci is a founding member of the Independent Forensic Expert Group (IFEG). He has provided forensic reports to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, the UN International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, and other international bodies, as well as to courts in several countries. He is a co-editor of the Istanbul Protocol, the UN standard for torture investigations, and a former detention doctor, of the International Committee of the Red Cross, a role that entailed examining people in detention.

Karen Kelly is director of Medical Examiner and Hospital Autopsy Services and an associate professor at the Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University, in the United States. She is a former director of Death Investigations, Region IV, in Alabama and a former medical examiner in several counties in the United States. She was a member of a 2014 mission that documented injuries caused by Israel’s attacks in Gaza and is a former International Health Section councillor of the American Public Health Association.