In its latest effort to keep asylum seekers from reaching the United States, the Trump administration enacted a new rule on July 16 that effectively bars anyone from seeking asylum in the United States who tries to cross the southern U.S. border after traveling through a third country. Instead, under the “third-country asylum rule,” the U.S. government will be dumping people seeking asylum onto other countries, such as Guatemala or Mexico, where there is no guarantee they will be safe or get a fair hearing.

Australians are all too familiar with government efforts to outsource their legal obligations onto other poorer countries that lack the capacity to cope with people seeking asylum and can’t protect them from resentful locals. They also know it doesn’t work.

The policy of barring asylum seekers from making a claim and sending them to another country is inhumane, expensive, and frequently results in human rights violations.

Offshoring also causes a new set of problems for countries trying to shirk their legal obligations, including protracted legal disputes, lost credibility in foreign policy, and violations of international law. And it needlessly prolongs the suffering of people who have already fled persecution by leaving them in limbo and exposing them to new dangers while they are separated from their loved ones.

This month marks the sixth anniversary of the Australian government’s reintroduction of “offshore processing” for all maritime asylum seekers. Under this policy, anyone seeking asylum in Australia after arriving by boat is sent to remote offshore camps on Papua New Guinea’s Manus Island or the island nation of Nauru. More than 3,000 people have been sent to these islands in an effort to keep them out of sight and out of mind.

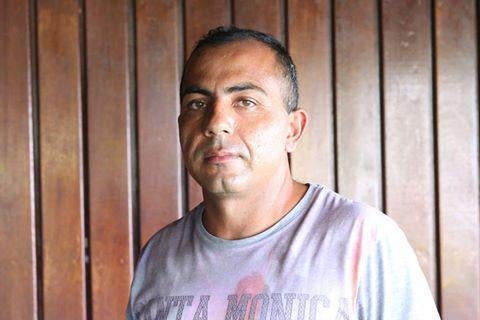

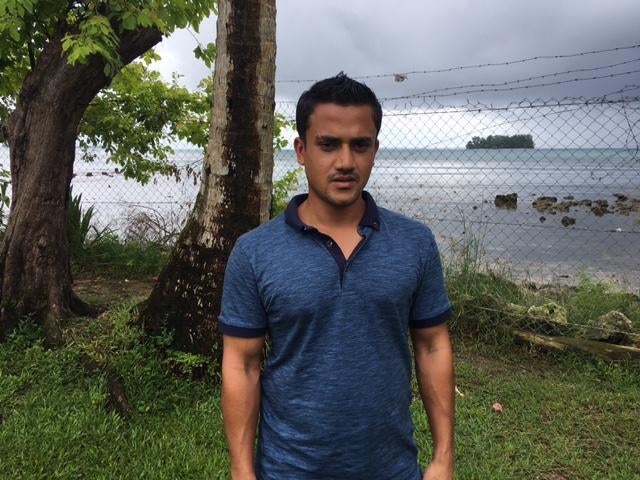

As with the United States’ new approach, Australia’s policy of offshore processing is designed to deter future migrants. Australian officials describe it as “harsh but effective.” Refugees sent to Manus Island and Nauru have a different take. “In Myanmar, the government shoots us,” an ethnic Rohingya man from Myanmar told me, “but here they kill us mentally.”

For years, while awaiting rulings on their refugee status, men, women, and children were detained in militarized camps, though they had not committed a crime. On Nauru, they slept in moldy tents with mice and cockroaches, in stifling tropical heat.

Eventually, legal proceedings forced the governments of Nauru and Papua New Guinea to open the gates of the detention centers and allow asylum seekers and recognized refugees to move into other facilities or into the surrounding community.

But when the detention centers closed, the violations didn’t end—they just changed in nature. There are still restrictions on free movement. The asylum seekers and refugees are easy targets for robberies, assaults, and violence—including sexual violence—and don’t receive much protection from local police. Health care is woefully inadequate, despite the acute need.

Like Mexico and Guatemala, Papua New Guinea has high crime rates, ineffective law enforcement, and a limited ability to provide services to poor and marginalized people.

In April 2016, Papua New Guinea’s Supreme Court found the detention of asylum seekers on Manus Island illegal and ordered the Papua New Guinean and Australian governments to immediately take steps to end the detention of asylum seekers there. In October 2017, both governments shut the main detention center and moved asylum seekers and refugees by force to other facilities closer to the main town of Lorengau.

Some locals started to resent the refugees and asylum seekers, who are living in facilities paid for by the Australian government. In 2017, groups of youths targeted refugees for robberies, sometimes violently, and local land owners protested the presence of the facilities, at times blocking the movement of people and goods to and from the sites, escalating tensions.

About 800 refugees and asylum seekers remain on Manus Island and Nauru. Most have been there since 2013, and those six years have taken a devastating toll on their physical and mental health. The United Nations refugee agency found in 2016 that 80 percent of the surveyed population on both islands suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, or anxiety.

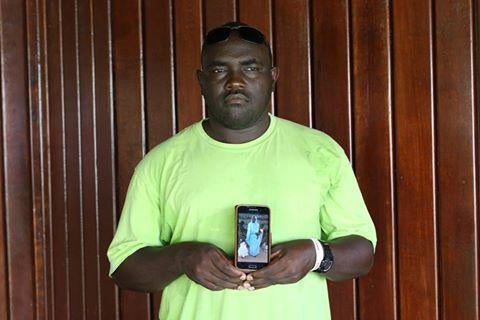

Twelve refugees and asylum-seekers have died on Manus Island and Nauru since 2013, six of them suicides. Despite the acute need, medical facilities are woefully inadequate and have proved unable to cope with their complex medical needs, especially mental health needs. Yet a new law authorizing evacuations of sick refugees and asylum-seekers to Australia on the advice of two doctors, passed after a damning coroner’s report into a death on Manus, has been hotly contested by politicians—including Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison. A Senate inquiry is now underway as part of an effort to repeal the medical evacuations law.

There’s also the enormous cost of keeping people in these miserable conditions. According to the Andrew & Renata Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law at the University of New South Wales, it costs more than $400,000 per year to keep someone on Manus or Nauru. In total, the Australian government has spent more than $3.9 billion on offshore processing. The government claims this expense is worth it to protect border security and because this is a fraction of the cost if tens of thousands of asylum-seekers arriving each year are detained onshore under the policy of mandatory detention. But if people seeking asylum are living in the local community on bridging visas while their asylum claims are processed, it costs only about $7,000 including the costs of basic health care—and many on bridging visas work and pay taxes, too.

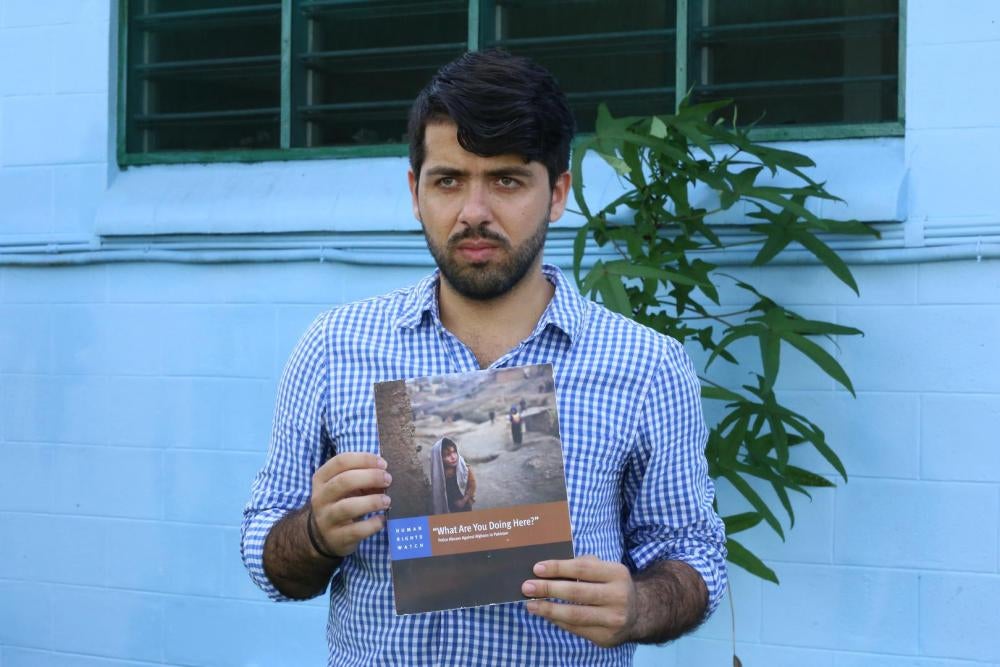

Deaths, sexual assaults, violence, and ongoing harsh conditions on Manus Island and Nauru have caused severe damage to Australia’s international reputation. The United Nations has repeatedly called on Australia to end offshore processing. In Geneva this June, Abdul Aziz Muhamat, a Sudanese refugee detained on Manus for more than five years, told the U.N. Human Rights Council: “Many hundreds are still being detained. And they are being completely destroyed, physically and mentally. We don’t have time. Not a day, not a week, not a month.”

The so-called Australian model of dealing with refugees and asylum-seekers should not become a template in the United States or anywhere else. It’s a model for misery, suffering, and death. Human Rights Watch research on Mexico has already found that thousands of asylum-seekers from Central America and elsewhere, including more than 4,780 children, are facing potentially dangerous and unlivable conditions after U.S. authorities returned them to Mexico.

With more than 70 million people displaced globally, there is no silver bullet to fixing the migration crisis. But countries like the United States and Australia, with proud histories of immigration, need to step up to their responsibilities, not push them elsewhere.

The Australian government recognized that its “Pacific Solution” could not last forever and desperately sought other countries to resettle the refugees. Since February 2013, the New Zealand government has offered to settle 150 refugees from Manus and Nauru each year. On July 19, New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern said the offer remained on the table but Australian officials repeatedly refused, claiming it would weaken border security by allowing a back door to Australia, given that New Zealand residents can easily travel to Australia.

Australia has no good reason to keep rejecting New Zealand’s offer, especially when Papua New Guinean Prime Minister James Marape said last week, “We need to establish a timeline going forward. … There are genuine refugees, and there are also nongenuine refugees. What happens to the rest of them we have in country? These are human beings we’re dealing with. We can’t leave them all hanging in space with no serious consideration into their future.”

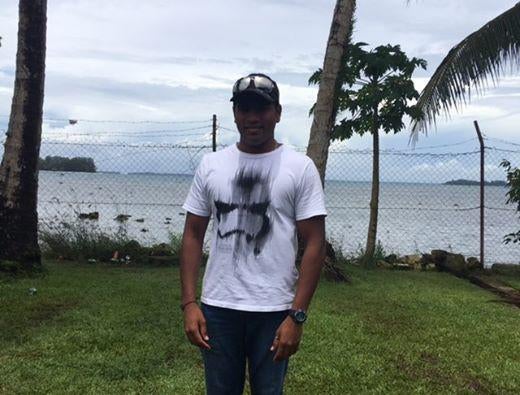

As Australia continues to rebuff its neighbor, the United States has helped the Australian government out as part of a U.S.-Australian resettlement deal brokered under the Obama administration and honored begrudgingly by President Donald Trump. As a result, about 500 refugees have managed to resettle from Manus Island and Nauru. Recently, I interviewed several young Rohingya men making new lives for themselves in Chicago. In return, Australia resettled a number of refugees from the United States, some of whom were detained for years in U.S. prisons on security grounds.

The new lives of the young Rohingya settled in Chicago show that despite years lost in limbo on remote tropical islands, they can find employment and safety and move on with their lives—something they could do in Australia, too, if Canberra would allow them to enter. One of them, Faisal, is now working as a waiter at a Chicago airport. Over breakfast at a diner on Chicago’s north side, he told me about his years on Nauru, describing it as “worse than prison.”

Faisal is now beyond excited at the thought of having a country to call his own. “I can’t wait to be an American,” he told me. “In Nauru, I was called by my boat number. I was called ‘refugee.’ I felt like I had that word plastered on my face. Here, the Chicagoans just call me Faisal, and if they don’t know my name, they even call me sir.”